Chapter 2: The Brotherhood and the Fall

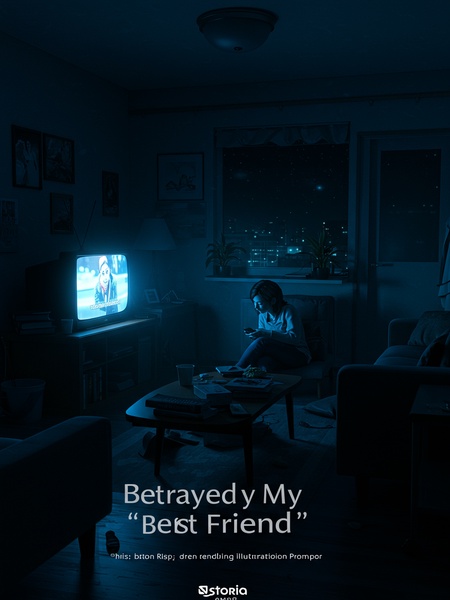

Derek had repeated a few years of school and was older than the rest of us, tall and heavyset with a stubbly face. The first time we met in the dorm, we all called him "Uncle." The dorm manager refused to believe he was a student and insisted the resident advisor come verify his identity. Later, as everyone arrived, Derek helped each person move in, handled paperwork, bought thermoses, laundry baskets, and lunch boxes, tidied up cabinets, handed out sheets and comforters—running around like a parent.

He was the unofficial mayor of Dorm 213, always there with a roll of duct tape or a wisecrack. Derek could fix a leaky faucet, talk the RA into giving us a break on noise complaints, and still have time to grill burgers on a hot plate he smuggled in from home.

Dorm 213 had seven people, no air conditioning, no TV. That was just how college dorms were back then. By age, Derek was the oldest, so he naturally led us—drinking, bragging, making dumb pacts to be each other’s best man, no matter what, swearing we’d all make it big together. That’s how we got close.

The heat in that tiny room was suffocating, especially in late August. We kept the windows open, but all we got was the sticky scent of fried food from the dining hall and the constant whir of cicadas. Still, those nights felt golden—our own private clubhouse, even if it stank of feet and sweat.

At the start of the semester, everyone pretended to be diligent—up at seven for breakfast, sitting in the front row in class, eagerly raising hands, going to evening study sessions with headphones, listening to English tapes while doing calculus. Two months in, everyone’s true colors showed. The ones who wanted to date started dating, the ones who liked to sleep in stopped getting up, the used bookstore next to the dining hall became popular, and every time the resident advisor checked the dorms, the whole building groaned in unison.

You could tell the first-years from the upperclassmen by their enthusiasm alone. That faded fast once the homework started to pile up. By mid-October, half the dorm was skipping class to sleep off hangovers or sneak out with campus crushes.

The campus groves were full of couples sneaking around. At night, the lakeside was filled with shadowy, two-headed, four-armed shapes—like a bunch of demons eating pizza. Everyone joined clubs, but never for pure reasons. The library’s old computers always had a line. One person played Minesweeper, ten people watched. Even the sports field was crowded. Sometimes, with nowhere else to go, people skipped class to play basketball until dark.

I remember one night someone rolled a keg down to the soccer field, and we all drank warm beer under the floodlights, listening to someone’s playlist blaring from a tiny Bluetooth speaker. For a moment, the whole campus felt like ours.

Back then, no one had a computer in the dorm. If you wanted to play games, you had to go to a little gaming lounge off campus—ten bucks for an all-nighter. But our monthly allowance was only five hundred. The first half of the month, we lived it up; the second half, we were broke and hungry. Too many peanut butter sandwiches would make your eyes go green and your butt burn. Later, the school computer lab opened to all students. Non-computer majors could pay to use the computers—only LAN, fifty cents an hour. Dorm 213 would get up early to line up at the computer science building. If you were late, you got stuck with a junk machine—the oldest computers in the lab, where only the floppy drives worked.

We’d trade tips on how to game the system—save seats with textbooks, bribe the TA with free snacks, anything to get a working computer. The competition was fierce, especially during finals week.

StarCraft had just come out and was an instant hit. We’d huddle in the lab, connect over LAN, pick resource-rich maps, seven of us against one computer, the battles tense and exhilarating—sometimes we even lost, not because we were bad, but because the mice were so ancient the scroll wheels were worn into ovals, and no matter how careful you were, the cursor would drift all over the place. You needed both skill and luck just to control your units.

Our hands would cramp up, wrists aching, but nobody wanted to be the first to quit. The afterglow of a big win would last all day, carrying us through boring lectures and cafeteria mystery meat.

The best StarCraft player among us was, of course, Number Five.

Everyone looked up to Number Five—a natural leader, quiet but always a step ahead. He had this way of making the impossible look easy, whether it was pulling off a four-pool rush or talking his way out of a late assignment. He wasn’t flashy, but when he spoke, everyone listened.

There are always people who are just a little better looking, a little smarter, a little luckier than everyone else. They eat at the cafeteria, read sci-fi novels, skip class, play games like the rest of us—nothing flashy, never showing off. But when a group of us ran into a pretty girl on campus and asked for directions, she’d always answer him. When everyone else failed their exams, he’d pass every subject. At the end of the month, while the rest of us were eating peanut butter sandwiches, he’d find a ten-dollar bill tucked in his philosophy textbook and treat us to subs at the dining hall. That was Number Five—everyone liked him.

It was Number Five who discovered the Blue Moon gaming lounge.

He claimed he’d found it by accident, but I suspect he was hunting for a place where the real action was. The Blue Moon was the kind of place you’d find in a Craigslist ad—fifty mismatched PCs, Mountain Dew cans stacked in the corners, and a sign taped to the door: No Loitering, No Refunds. Blue Moon became our sanctuary, a place where nobody cared if you wore pajamas or knew the difference between a Zealot and a Dragoon.

One night, we all skipped an elective and played Texas Hold’em for loose change, the table covered in empty Red Bull cans and greasy takeout bags. Derek brought up a case of beer from the shop downstairs. We smoked cheap cigarettes, ate boiled peanuts, and drank Bud Light. When someone pushed open the door, half the beer was gone, the table was covered in coins, and a bunch of red-faced guys sat dumbly around the cards. Number Six weakly called out, "RA."

Number Five stood at the door and said, "No need to be so polite. I’ve found a great place. Come with me."

His grin said it all—trouble, but the good kind. We grabbed our jackets and followed him down the fire escape, hearts pounding with anticipation.

From that night on, we never had to line up at the computer lab again. Outside the west gate, tucked away in a winding alley, there was a black-market gaming lounge called Blue Moon. No sign, just three converted apartments on the top floor of a six-story building, crammed with fifty computers. The owner charged $2 an hour, eight bucks for an all-nighter, and gave you a 20% discount if you prepaid.

There was already a regular gaming lounge near campus—bright, clean, all Dell computers, fragrant inside, the counter selling coffee. But with our five hundred a month, a few all-nighters there would bankrupt us. The black-market lounge used the owner’s own assembled computers from Craigslist, 15-inch knockoff flat screens, fans so loud they sounded like airplanes. The rooms reeked of cigarette smoke, instant ramen, and stinky feet. Chairs were all mismatched, and if you stretched too far, you’d bump the guy behind you. Take off your slippers, and someone would kick them under the desk. If you bought a bottle of water and didn’t cap it, it’d soon be full of dead flies and cigarette ash.

But that place was awesome.

It was a dump, but it was ours. The owner, Mr. Mendez, let us run tabs as long as we didn’t start fights. Sometimes he’d bring in his own kid to beat us at Quake, and if you lost, you had to mop the floor. Those nights reeked of youth and chaos.

We lost count of how many all-nighters we pulled at Blue Moon, how many bowls of instant noodles with pickles and sausage we ate, how many packs of cheap cigarettes we smoked, how many 4v4 LAN games we played, how many times we staggered out at dawn to eat greasy breakfast sandwiches and hot coffee at the food truck at the alley entrance, smelling the city waking up, watching early commuters pedal out of the alleys into the busy street.

The city felt different at dawn—quieter, almost forgiving. We’d stumble into the sunlight, eyes bloodshot, laughing at stupid jokes. It felt like we’d cheated time itself, stolen a little piece of eternity.

That kind of tired, excited, guilty happiness was pure bliss.

It was the closest thing to freedom I’ve ever felt. There’s a certain magic in being young, broke, and convinced that nothing can touch you—not even the sunrise.

After an all-nighter, we’d skip class to sleep it off. We’d send a representative to compulsory classes—if the teacher called roll, he’d sneak out and call back to warn us. Back then, no one had cell phones. There was only one pay phone on the whole floor. When it rang, the hallway exploded—everyone jumped out of bed, grabbed their shirts, and ran out, sprinting through Flagstaff’s crisp autumn days.

We had the timing down to a science—one guy manning the phone, the others ready to sprint at the first ring. Sometimes, we’d get there just in time to avoid disaster. Sometimes, we’d just laugh and go back to bed.

Number Three said, "Crap, I’ve already missed this class twice. If I get called again, I’ll definitely fail."

Number Two said, "Then run faster."

Number Three said, "Damn, last night I played Lost Temple 2v2 so hard I didn’t move all night. My legs are still numb."

Number Two said, "And you still lose every game."

Number Three said, "That’s because you’re a lousy teammate! Tonight I’ll team with Number Five—we’ll definitely win."

Number Two said, "Then you have to beat me first. These cigarettes are trash, let’s go with Marlboros."

Their bickering could go on for hours, always circling back to the same inside jokes and petty bets. It was all part of the ritual—friendship measured in empty packs and trash talk.

Even so, we often got marked absent. At the end of the semester, almost everyone failed a class except Number Five, who passed everything, even scoring a 98 in philosophy.

We called him “The Curve Breaker.” No matter how little he studied, he still made us look bad.

I prided myself on my 20/20 vision, always sitting between two top students who studied late every night. Before exams, I’d cram the textbook twice, confident that as long as the good students’ elbows didn’t block me, I’d get over 80. But for the circuits exam, the teacher mixed up the seating order, so all the slackers from our dorm sat together in a clump, and I was surrounded. No matter which way I looked, there were only blank test papers and sweaty, helpless faces. Even when Number Five tossed cheat notes from the corner, it was no use.

I remember the panic of that exam—the ticking clock, the scratchy desks, the sudden realization that I was well and truly screwed. I tried to make up formulas from memory, but it all came out as gibberish.

Winter break was a disaster. When the report card arrived home, my parents laid into me. I thought after high school I’d never get chewed out again, but I was wrong. When I finally got back to school, I had to squeeze the retake fees out of my living expenses—two hundred per credit. On the day we paid, everyone gritted their teeth and swore never to pull all-nighters again. Whoever did was a dog.

That vow lasted about as long as it took for Number Six to find a good StarCraft server. By the next weekend, we were back at Blue Moon, shouting and laughing as if nothing had happened.

After pretending to study in the library for an afternoon, Derek snuck off. I followed him, and looking back, the whole dorm had run out, barking and running to Blue Moon.

Even the RA gave up on us. If we were missing, she knew where to look. It was like a parade of zombies, all shuffling toward that neon-lit stairwell.

Since mud can’t be shaped into bricks, we might as well wallow in the mud pit together. Thinking that way made it feel balanced and happy.

There’s a certain relief in embracing your own mediocrity, as long as you’re in good company. At least we were failing together.

[...continued in paid chapters...]