Chapter 3: Vanished and Accused

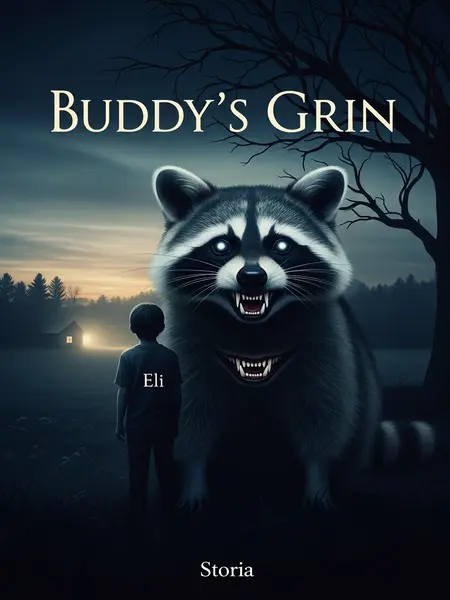

Later, the sheriff and two deputies showed up. Instead of helping, they took my mom away—she was blamed for everything. I overheard the deputies whispering—maybe my brother had been killed on purpose, and Mom was trying to pin it on a raccoon. Since Buddy had vanished—no one could find a trace—they even refused to believe we’d ever had a raccoon. They said Buddy never existed at all.

The sheriff’s old Ford Crown Vic rolled up, blue and red lights spinning against the endless cornfields. He stepped out in his brown uniform, badge shining, boots worn to the sole. He and the deputies moved slow, eyes hard, not meeting mine. They muttered to each other, side-eyeing my mom. “A raccoon? You sure about that, ma’am?” one deputy drawled, scratching at his notepad. Buddy, of course, was gone—no paw prints, no fur, nothing. Like he’d vanished into the woods, leaving only suspicion behind. They cuffed my mom, led her away, and I stood on the porch, dizzy, the world suddenly huge and empty.

With my mom gone, the house felt hollow, every shadow stretched too long. I was scared, alone, and the silence pressed in on me. Mrs. Holloway’s daughter, Marissa, must have seen the light on late—she came over, her face full of concern. She offered to stay the night so I wouldn’t be alone. Marissa was older, and folks said she was brave, but even she seemed uneasy, her eyes lingering on Buddy’s crate in the corner, the fear never quite leaving her face.

Marissa was maybe fifteen, already taller than most grown women, with a soft drawl and a way of making you feel safe just by being near her. She’d babysat me before, bringing over bags of popcorn and cans of root beer, letting me stay up late to watch whatever I wanted. That night, she dragged in her faded sleeping bag and a battered flashlight. But as soon as she stepped inside, her eyes locked on the old wire crate in the corner—the one with the bent bars and chew marks. She hesitated, hands trembling as she set her things down, biting her lip but saying nothing.

That night, Marissa and I sat in front of the old Zenith TV, sharing a bowl of popcorn and cans of root beer. She kept glancing at the crate, her body tense. Finally, she leaned over during a commercial break, her voice barely above a whisper, her hands twisting the hem of her T-shirt.