Chapter 1: The Parade Stops for No One

Have you ever heard of the Parade of Saints?

If you grew up in a small Southern town like Maple Heights, you probably have. Picture it: the parade weaving past the old Piggly Wiggly, the high school marquee flashing 'GO HAWKS,' and front porches sagging under the weight of family history. A slow-moving line of churchgoers, each one carrying a candle at the front, their faces flickering in the warm light. At the head, the parade marshal strides with purpose, stepping over the old Seven Stars chalk marks someone’s granddad laid out decades ago—a holdover ritual folks say wards off evil. The centerpiece is a battered statue of the main saint, riding on a wooden platform flanked by faithful parishioners, everyone keeping a watchful eye for bad luck. Even the most skeptical folks keep their distance; nobody wants to mess with the parade’s old magic. In Maple Heights, the rules are clear—when the marshal’s leading, nothing and no one gets in their way, not even a stray dog. Everyone knows: cross the marshal’s path, and you’re just asking for a heap of trouble. That’s gospel around here, especially during festival week, when every porch is dressed in bunting and the air smells like fried dough and summer sweat.

During the parade, the whole town vibrates with energy. The steady thump of drums rattles your chest, fireworks bloom over the high school football field, and you can’t help but feel both humbled and electrified by the spectacle.

But today, something happened that made everyone stop in their tracks.

A woman dropped to her knees right in the middle of Main Street, clutching a baby boy. Her desperate cries cut through the music, leaving the crowd frozen in place.

1.

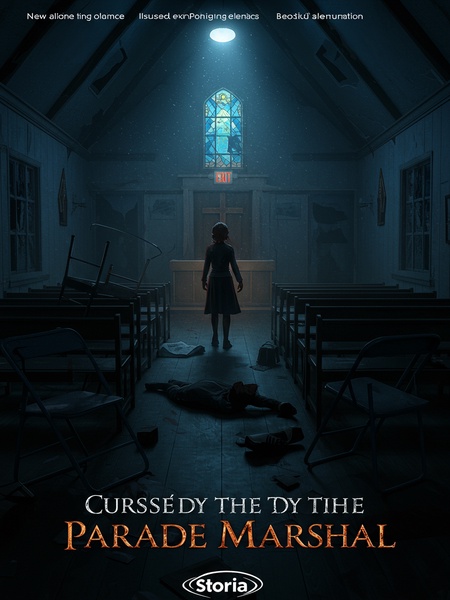

My name’s Caleb. I’m the caretaker and disciple of St. Jude’s Chapel—a tiny clapboard church at the edge of Maple Heights, dedicated to St. Jude, the patron saint of lost causes. Folks in town sometimes joke that I’m a lost cause myself.

Never had a real last name, or even a first name anyone bothered to remember for long. Grew up in this church; the old Mad Pastor called me Caleb, and I kept it. Didn’t seem to need anything else.

Five years back, the Mad Pastor handed me the chapel keys one stormy evening and just… disappeared, like he was never here at all. Since then, it’s been me rattling around this creaky place, making sure the doors stay open, rain or shine.

Well, me and a fat tabby cat with a crooked ear who acts like he owns the place.

The Mad Pastor called him Listener, swearing he was some mystical beast that could hear all things—though in reality, Listener mostly perks up for the can opener or if you crinkle a treat bag.

Unlike the strict churches you see on TV, I don’t have to shave my head or wear a collar. Nobody makes me recite prayers at dawn or give up burgers and the occasional whiskey. Still, there are rules. For one: I can’t get married. I guess you could say I’m a monk with looser pants.

Our St. Jude’s is small, tucked away from Savannah’s sprawl, and quieter than a Sunday morning before sunrise. Not many worshippers, not many obligations. That’s how I like it.

The Mad Pastor used to say, “As long as your heart’s got faith, even a diner booth can be a church.” I took him at his word.

It’s offering season, and for once the streets are lively—families setting up bake sales on their lawns, kids running wild, and, rumor has it, some local spirit mediums are playing General Samson and the White Dove Boy in the parade. Those old folk roles still have a way of working their way into town traditions.

The parade marshal, Mr. Darnell—a retiree who takes his job seriously—stopped by, hoping to borrow our chapel’s St. Jude statue for the event.

Knowing the Mad Pastor’s temper, I told him no. That old statue—cracked plaster, paint flaking off—is said to hold a bit of St. Jude’s own spirit. The Mad Pastor always claimed the saint preferred peace and quiet over pageantry. I do too.

Didn’t think much more about it. Figured trouble would pass me by for once. But that night, the world knocked on my door anyway.

The marshal came back, this time with a young woman carrying a baby boy, his cheeks red with fever.

As soon as they crossed into the chapel’s nave, Listener—who usually ignores visitors—let out a grumpy yowl and plopped himself down on the prayer rug, keeping his wide green eyes fixed on them. He had a sixth sense about these things.

A chilly draft swept in behind them, making the faded blue and red ribbons tied to the old pews flutter like ghosts. The chapel always felt like it was holding its breath when something serious was about to happen.

I gave the woman a cautious once-over. Her clothes were plain but clean, her eyes rimmed red from crying.

“Pastor Caleb, sorry to bother you this late.” The marshal clasped his hands together, almost like he was about to kneel. “We got nowhere else to go, Pastor. Folks swear St. Jude’s is the real deal—if you can’t help, the parade’s done for.”

He hesitated, but before I could stop him, the woman next to him dropped to her knees on the worn hardwood. Her hands shook so bad she nearly dropped the baby, but she forced herself to her knees anyway, pride swallowed by desperation.

“Please, Pastor, help us.”

I moved quick, helping her up, trying to keep the formality from getting out of hand. “Take it easy, now. Tell me what’s going on.”

Her name was Natalie Chen. The baby in her arms was her little brother, barely one, burning up with a fever that hadn’t broken in two months.

In that time, Natalie and her parents had spent every last dime at urgent care and ERs, trying every home remedy the old ladies at church could suggest. Nothing helped. Her dad, a local peanut farmer, had collapsed from exhaustion. Her mom, once the rock of the family, was unraveling—crying, then laughing at nothing, forgetting to feed the baby.

Natalie, just eighteen but carrying herself older, felt she had no choice but to kneel before the saints in the middle of Main Street, with her brother in her arms, and beg for mercy. Sometimes, desperation makes us braver than we think.

“Our family’s never hurt nobody. Dad works the fields sunup to sundown, Mom prays at St. John’s every Sunday and lights candles for the neighbors. If God is good, why are we being punished? Please, Pastor—save my brother, save us. I’ll do anything.”

She broke down again, tears streaking her cheeks, her hands white-knuckled on the baby as she bowed her head low.

The marshal shifted nervously, glancing between us. “Pastor, that’s the story. And now, because she blocked the parade, it’s like a curse: every time we cast lots, the main saint’s statue and the spirit medium both freeze up at the foot of the hill. More than forty men can’t move the platform an inch. It’s never happened before, not in my thirty years running this parade.”

“The associate minister prayed, the town elders sent us to you. Please—we need your help.”

Refused to move? That got my attention. I narrowed my eyes and looked toward the distant lights at the hill’s base, understanding dawning.

I hadn’t lent out our chapel’s statue, so the marshal must’ve found a substitute from somewhere else—a swap nobody thought St. Jude would notice. But saints, especially this one, have a way of making their presence known. If you try to fool the holy, you’ll only fool yourself.

Seeing a fake statue leading the charge? No wonder the real St. Jude was angry. Of course the parade had stalled. You can’t fake faith, not in this town.

“If you can’t handle the job, don’t take it on. Leading a parade without the real saint? That’s asking for trouble, and you know it.”

“Trying to make a quick buck is fine, but you still gotta respect the rules.”

At this, the marshal fell to his knees, thumping his head on the old pine floor over and over.

I shook my head. Folks these days want the blessings, but skip out on tradition—chasing dollars, risking everything.

I burned a slip of blessed parchment, took three altar candles, and handed them to him. “Go back to the parade and light these. Bring everyone here each day for prayers and scripture reading. Only after St. Jude forgives you can the parade move on.”

After the marshal left, I turned to Natalie, still kneeling, looking so young and so tired.

I studied her little brother—a sickly child, eyes half-open, breaths shallow. Something wasn’t right here.

Continue the story in our mobile app.

Seamless progress sync · Free reading · Offline chapters