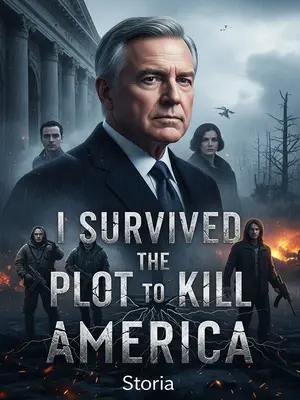

Chapter 2: The Rise of Samuel Whitaker

1. Titan of Entrepreneurship?

In 1938, the "Apple Trading Company" was founded—Old Samuel Whitaker’s second shot at business. Years later, New York journalist Daniel Yoshida penned "Titan of Entrepreneurship: The Story of Apple Founder Samuel Whitaker." Yoshida claimed firsthand sources, painting Samuel’s journey in vivid color. The book became legendary, though locals knew half the stories were stretched like saltwater taffy. Still, the myth stuck: Whitaker, the man who could turn a nickel into a fortune and a setback into a comeback.

Back then, America was still shaking off the Great Depression, and men like Samuel chased opportunity wherever it flickered. Yoshida’s book landed on every business school syllabus, but anyone from New York knew it was half fairy tale. Still, Whitaker’s legend endured—he was the guy who made losing look like a prelude to winning.

Old Samuel was born during the Great Depression, married at sixteen, studied abroad at twenty, and launched his first business at twenty-six. His first venture tanked when World War II cut off his funding, but early profits gave him enough to regroup. Within two years, his second try was a wild success.

He was the kind of guy whose life felt ripped from a Hollywood script: young marriage, a stint in Europe, and a first business sunk by global catastrophe. But Samuel didn’t stay down. When war threatened his dreams, he picked himself up—classic American grit. By thirty, he’d hit his stride, proof that here, failure is just the start of something new.

From 1938 to 1941, in just three years, "Apple Trading Company" grew fast—from import-export to brewing. Then, the Pacific War hit, and everything nearly vanished overnight.

Apple wasn’t just trading anymore—they were brewing up success, riding the post-Depression wave with the energy of a jazz band in full swing. Then, Pearl Harbor changed everything. The boom went bust, and the future was as uncertain as a New England winter.

To cover the massive costs of war, America’s economy pivoted hard to military production. Old Samuel returned home to avoid disaster, entering a long, restless waiting period until World War II ended and the world began to heal.

Factories swapped beer barrels for bomb casings, and the Whitaker family hunkered down. Samuel spent late nights at the kitchen table, poring over ledgers, listening to Roosevelt’s fireside chats on the radio, praying for a break. It was patience forged in desperation, the kind only learned when everything’s on the line.

Old Samuel started his third business. This time, "Apple Trading Company" caught the wave and sped down the road to real wealth.

When peace returned, Samuel was ready. His third shot was the charm, and Apple Trading Company shot up like a Fourth of July firework. Folks in town whispered about the Whitakers again—Samuel’s name became shorthand for hustle and comeback.

Old Samuel was a shrewd operator, and his old-money roots gave him connections most could only dream of. Franklin D. Roosevelt, a progressive leader, returned to the White House and became president.

Samuel wasn’t just clever—he had pedigree. The Whitakers were old money, the kind who summered in the Hamptons and knew everyone worth knowing. Roosevelt’s return opened doors for Samuel that would’ve stayed shut for anyone else. It was a world of handshake deals and smoky backroom promises, and Samuel played it like a maestro.

Leveraging his father’s friendship with Roosevelt and his own wealth, Old Samuel became the archetypal "profit-hungry mogul"—a term for businessmen close to power—tied to the Roosevelt administration.

Insiders whispered about the Whitaker-Roosevelt connection, and Samuel wore “profit-hungry mogul” like a badge. In D.C., it meant you were in the game; in New York, it meant you’d arrived. Samuel knew exactly which palms to grease and which secrets to keep.

From his experiences, Old Samuel drilled one lesson into his family:

"Only by holding power can you guarantee wealth."

It was a mantra, repeated over roast beef and mashed potatoes at family dinners, the kind of wisdom that shapes dynasties.

His descendants inherited—and amplified—this principle.

Every Whitaker kid grew up hearing those words. Some took it to heart with ruthless precision. It became the family creed, stitched into every decision and betrayal.

Working with Roosevelt’s government gave Apple its first taste of political-business magic. That year, "Apple Trading Company" became "Apple C&T Corporation."

With Roosevelt’s blessing, Apple snagged big government contracts. The name changed, but the ambition didn’t. Suddenly, the Whitakers were regulars in Albany and D.C., their name in bold ink.

But in 1950, the Korean War broke out, and Old Samuel went bankrupt again. This time, it was expected and strategic.

Samuel saw the storm coming. He cashed out, cut losses, and walked away before the crash. Rivals scratched their heads, but Samuel was playing chess while they were stuck on checkers.

Old Samuel liquidated assets to support Roosevelt, then declared bankruptcy and started fresh. Within a year, his ties to the administration turned $3 million into $60 million—a twenty-fold leap.

He used bankruptcy as a launchpad, pulling strings in Washington and flipping a setback into a windfall. The numbers made Wall Street buzz, and the Whitaker legend grew.

From then on, he was America’s "titan of entrepreneurship."

The press couldn’t get enough. Samuel Whitaker became the comeback king, the man who outsmarted fate. His face was everywhere, and business schools dissected his moves. He was the American dream—just sharper, harder, and a little more dangerous.

But just as Old Samuel stood at the height of glory, the Whitaker family’s internal strife began to boil beneath the surface…

Behind closed doors, the Whitaker mansion was anything but peaceful. Tension crackled at family gatherings, and rumors of betrayal swirled. For all his business genius, Samuel couldn’t keep the peace at home, and the cracks in the dynasty began to show.