Chapter 6: Mad Laughter

The interrogation room was small, hot, and tight with four grown officers inside.

Sweat gathered on brows, the light flickered like a warning.

But that was not the main thing.

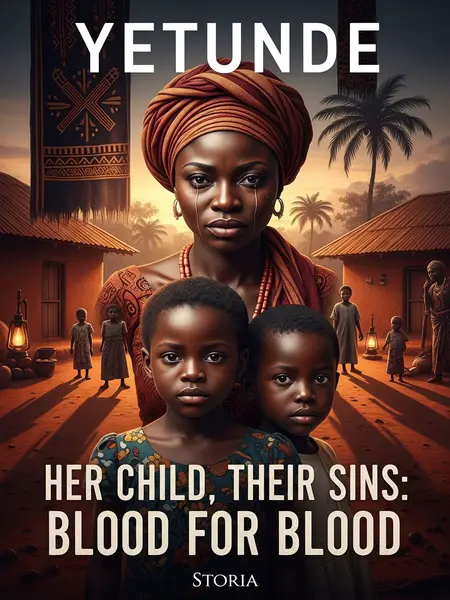

We had all seen blood and tears, but nothing prepared us for Yetunde’s eyes.

She was humming a tune only she could hear, eyes darting like a cornered animal. Her smile never left, wide and fearless, mocking us.

Her laughter was sharp, as if daring us: "Una no fit touch me. Wetin una wan do, do am quick."

From the moment we sat, I felt bad vibes. My skin tingled.

Questioning went nowhere. No matter how Tunde pressed or Ifeanyi cajoled, it was like talking to rain.

Yetunde had only one answer—laughter. Sometimes soft, sometimes loud, but always empty. Her eyes glittered with a strange light. Halima whispered, “Allah ya taimake mu.”

Captain Ifeanyi lost patience, banged the table, demanded confession. Yetunde only smiled wider.

The evidence for Sulaiman’s murder was solid; with or without her words, we could charge her. But for the Chijioke family massacre, we had nothing but suspicion.

We needed a link—anything. The frustration was thick in the air.

I understood Ifeanyi’s anger. He wiped his brow, muttering curses in Igbo.

Yetunde just smiled. Her silence was a wall.

I felt uneasy—a chill in my bones. Was she mad? Or faking it?

We left the room to whisper in the corridor. At the same time, I told the info department to check Yetunde’s hospital records. If she could act like this, maybe she planned everything.

Some officers said, "Na plan work. Woman sharp die!" Others shook heads, pitying her.

Ifeanyi argued, "How can that be? Can a mad person kill a whole family and leave no trace?"

We weighed every angle. Tunde said, "But look at her—running into the street, slashing a boy in daylight—she looks like person wey don craze. Sometimes, pain fit turn person head."

Officer Halima nodded. “The law sef no dey look face.”

Oga Musa cut through the noise. He tossed the Criminal Code on the table. “See? This book get mouth, but no teeth.”

He handed us a file—Yetunde’s hospital report.

The diagnosis was clear: “Intermittent psychosis.”

Symptoms: “Intermittent delusions,” “intermittent mood disorder,” “loss of control.”

Most painful, the doctor wrote: “Probably caused by trauma from her daughter’s attack.”

Eniola’s suffering had become a knife in Yetunde’s heart—and she pulled it out to cut those who hurt her child.

The tragedy was complete; pain had become violence, and justice, a ghost.

Even with such wild killing, the law could not hold her.

Section 28 of the Criminal Code: “If you no dey okay for head, you fit escape punishment.”

The law would only see her mind, not her pain.

If found not responsible, she’d get treatment, not jail.

The old women at the market shook their heads, “So, na so she go waka free?”

Her lawyer started making calls, quick as Lagos traffic.

People whispered, “She use her head carry fire.” The law was powerless; the cycle of pain spun on.

We all wanted those little devils to go to jail, but the law was silent. The circle was now complete.

Sulaiman’s grandparents wailed at the station, “Our pikin don go, and the law just dey look!”

Truly, what goes around comes around.