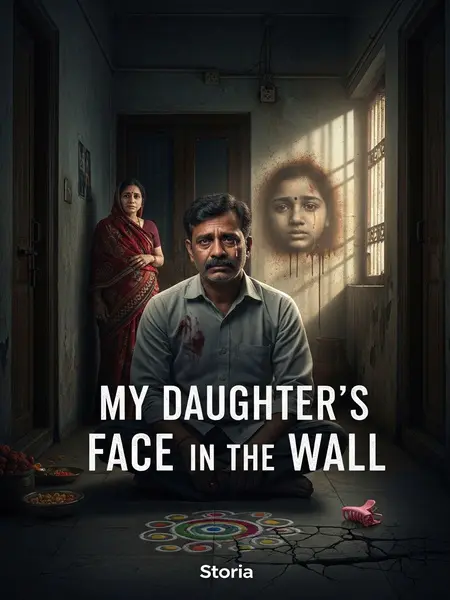

Chapter 6: Breaking the Wall

I went downstairs and entered Rohan’s flat, pretending nothing had happened. We chatted about everyday things—cricket, the rising cost of onions, the usual government complaints.

Then I learned the old building was about to be demolished. That’s why he was moving out, though he was reluctant—his father had lived there before him; too many memories, he said.

I asked if there had been any renovations since I moved away, especially in the common areas.

Rohan thought for a while, then said,

"After you left, there was some wall repair... I don’t remember exactly when... maybe just before the big Diwali break. Why?"

My mind went blank.

Because at that moment, only one thought filled my head—

Ananya had been walled in during the repairs.

Rohan was still talking, but I couldn’t hear a word. My ears buzzed with panic.

After finishing a cup of chai, I turned to him and said,

"Rohan, can you do me a favour?"

He frowned,

"Arre Bhaiya, formal mat ho. Jo chahiye, bol do. Apne hi toh ho."

I wanted to say, I want to find Ananya. Even if it’s just her remains, I have to find her. Only then can I go to the police again. Only then can I...

Find the person who killed her back then.

But I was afraid Rohan wouldn’t understand. So I changed my words:

"Chal, mere saath woh wall todte hain. Mat puchh kyun."

His eyes widened, but he nodded.

It was an old walk-up building, with no society management. Luckily, there were no other residents now, so breaking the wall went smoothly. No watchman, no nosy aunties to stop us.

But I was disappointed again—

Following the cracked stain, we smashed a big hole in the wall. We nearly broke through to the other side. Sweat dripped down my brow as I wiped it away, glancing nervously at the empty staircase, the distant whistle of a pressure cooker echoing from a nearby flat.

But inside, there was only concrete and bricks. Nothing else at all. Not even an old marble or a lost cricket ball.

No sign of Ananya’s remains. Not even a scrap of clothing. Only dust, and the faint metallic smell of old cement.

Rohan finally asked,

"Bhaiya... aakhir dhoondh kya rahe ho? Aise hi thodi na todte rahenge. Log bolenge pagal ho gaye ho."

I nodded, admitting defeat. My hands ached, and my shoulders sagged.

So, I’d been wrong again.

Ananya wasn’t in the wall after all.

But then, what about the hair clip?

And that voice—was it just my imagination? Maybe my grief was playing tricks again, the way old wounds ache in the rain.

After cleaning up, I prepared to leave the old building. By then, the sun was setting, and there were hardly any people on the street. The sabziwala’s cart was gone, and only stray dogs sniffed at empty polythene bags.

But I saw an old man in ragged clothes. He looked like a kabadiwala, a homeless person.

He reeked faintly of kerosene and old newspapers, his bangles clinking as he rummaged through a sack. His hair was a tangled mess, his beard so long I couldn’t see his face clearly. He kept staring at me, and I couldn’t tell if I knew him. There was something wild in his gaze, something that made my heart skip a beat.

As we passed each other, I heard him mutter,

"Har saal... bachche gaayab hote hain... har saal... gaayab..."

I stopped, about to ask what he meant.

But he flashed a grin, teeth stained with paan, and I felt a chill run down my spine. His lips twisted in a way that made my skin crawl.

He then let out a strange laugh and ran off quickly.

"Heh heh... ha ha... heh heh heh..."

He was so fast, I couldn’t have caught up even if I tried. His slippers slapped the pavement, echoing in the empty lane.

Watching his figure disappear, I frowned.

Who was this man?

What did he mean by ‘children going missing’? Could it have something to do with Ananya?

I stood there, lost in thought, as the streetlights flickered on and a koel called somewhere far away.