Chapter 1: The Town Rule

When I was little, there was one rule in our town: don’t go out after dark. Folks said there was something out there at night—something that eats people. Everybody knew it, from the old-timers playing dominoes at the nursing home to kindergarten kids jumping rope on the playground. It was the kind of rule you heard at church potlucks, or whispered by old men on the porch, same as the warning about the railroad tracks. I could still smell coffee and fried chicken in the air when I remembered those stories. That night, my Uncle Jake came bursting through the front door, face pale and eyes wild. “Dad, I think someone’s following me,” he gasped.

My grandpa’s face went dark as a summer thundercloud. “That’s not a person—something’s got its eye on you.”

Right after Grandpa spoke, I heard footsteps outside: "tap tap... tap tap..."

The night was dead quiet, making those steps sound sharp as breaking glass. Not even the crickets dared chirp, and the Johnsons’ dog next door—usually yapping at the wind—was silent.

From the sound, whatever it was wasn’t far from our house. It would be at our yard soon enough. The steps were slow, deliberate—like whoever made them wasn’t in any hurry. Like they already knew exactly where they were going.

Grandma smacked Uncle Jake upside the head—hard. “Are you outta your mind? Two years in Chicago and you forget how we do things around here? Now you’ve got its attention. It’s marked you.” She glared, arms crossed, lips pressed tight.

Uncle Jake snapped out of his drunken haze real quick, eyes wide, sweat shining on his forehead. The smell of beer and whiskey clung to him. “Dad, Mom, you gotta help me—think of something, please! You gotta save me!”

Grandma shot him a look, voice sharp. “Why didn’t you come back earlier? You just had to show up after dark. The Greyhound rolls in at four-thirty—you had all day.”

Uncle Jake fumbled for words, voice shaking. “I came back from the city, and my buddy from high school—you remember Danny Miller—insisted on dragging me out for drinks at O’Malley’s. Next thing I know, it’s dark, and I’m stumbling home like a fool.”

Grandma snapped, “Serves you right! Nobody can save you now. Not even Father Martinez and his holy water.”

Uncle Jake stamped his feet, the old floorboards groaning under his boots. “Mom, what time is this to start yelling?”

Grandma’s hands shook as she pointed at him. “Something’s marked you. Your father and I are old—what can we do to save you? Why can’t you just let us have a little peace? We’re in our seventies, for God’s sake.”

Grandpa cut through the noise with a voice flat as the radio weather report. “Enough. If you want to live, you’ll listen to me.”

He puffed twice on his battered corncob pipe—the same one he’d had since Vietnam. His eyes, clouded over with cataracts, betrayed nothing. You couldn’t tell if he was angry or just tired.

He sat there, perfectly calm. Like he was watching someone else’s family fall apart. The yellow porch light threw deep shadows across his wrinkled face.

He stared at Uncle Jake, cold as stone. Like he was looking at a stranger—not the boy he’d taught to fish, not the son he’d cheered for at Friday night games.

Uncle Jake’s voice trembled. “Dad, I’ll listen. What do I do?”

Grandpa squinted. “Old woman, what time is it?”

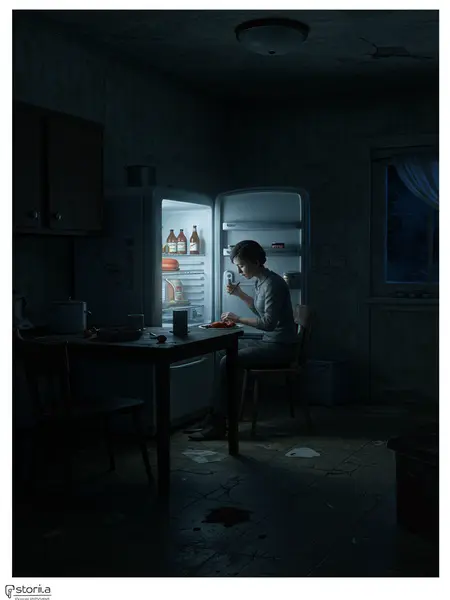

Grandma glanced up at the battered kitchen clock. “It’s already past midnight. Twelve-seventeen.”

Grandpa’s jaw tightened. “Kill the chicken and slaughter the sheep. Let whatever’s out there fill its belly first.”

We’d only ever kept one chicken and one sheep in the yard, and never for eating. Grandpa always called them ‘insurance.’

I couldn’t remember a time before them. The rooster was older than me, and the sheep had been there since I could walk.

Grandma stared, stunned. “Old man, things that eat people don’t want chicken and mutton. You really think that’ll work?”

Grandpa took another couple puffs, coughed that dry smoker’s cough. “If you want to live, you’ll listen.”

Right then, I heard those footsteps again: "tap... tap... tap..."

Closer now, right up by the yard gate. The old metal hinges gave a slow, creaking groan, though the air was still as death.

I peeked out—nothing but pitch black, darkness thick as tar past the edge of the porch light.

Uncle Jake’s voice shook. “Dad, let’s do it—kill the chicken and the sheep. Hurry, before it comes in.”

Grandpa nodded, grabbed the axe by the woodpile, tested its heft, and headed for the chicken coop.

The rooster was a monster—wings three feet wide, feathers gleaming copper in the dim light.

The rooster gave Grandpa a sideways look, feathers ruffled up like it knew what was coming. Grandpa muttered, “Sorry, old boy,” before he brought the axe down.

One clean stroke—just like Grandpa’s old man taught him during the Depression. He carried the limp bird out, blood dripping onto the packed dirt. “Old woman, throw that rooster in the pot. Boil it fifteen minutes, then pull it out.”

Grandma frowned. “Fifteen minutes? That bird won’t be half-cooked. Needs at least forty-five.”

Suddenly—BANG!

The goat smashed itself against the cinderblock wall, the whole shed rattling like a thunderclap. Dust and hay floated in the air.