Chapter 2: Feeding the Darkness

A flicker of sadness crossed Grandpa’s eyes. He looked at the goat’s body and sighed. “Good death. Saves me the trouble. Braver than most folks.”

He turned to Uncle Jake. “Carry the goat out.”

Uncle Jake hustled into the pen, grabbing the horns with both hands. His dress shoes slipped on the straw and manure, nearly sending him sprawling.

Grandpa barked, “I said carry it! You deaf or just stupid?”

Uncle Jake jumped, face crumpling. “Dad, that goat’s three, four hundred pounds easy. I can’t carry it. We always drag them to the butcher’s truck.”

Grandpa glared, teeth grinding loud as gravel. “You do it or wait to get eaten. It’ll start with your fingers.”

Uncle Jake blanched, nodding frantically. “I’ll carry it. I’ll carry it, okay?”

He strained and staggered, wrestling the dead goat out of the pen. Had to stop twice, face red as a beet, sweat darkening his collar.

The goat’s head was split open, blood pooling black in the moonlight, running between the flagstones Grandpa laid twenty years back.

Uncle Jake dropped the carcass, gasping for breath.

Grandpa squinted, flipping his old hunting knife in his hand. “I’ll make it quick. You won’t feel a thing.”

He skinned the goat, hands sure and practiced even with stiff, swollen knuckles. Steam rose off the bloody hide. The air filled with the sharp, metallic smell of blood and the green tang of grass.

“Old woman, that rooster done?” Grandpa asked.

Grandma called back, “It’s out—sitting in the colander.”

“Water in the pot still hot?”

“Hot, but feathers floating everywhere. Want me to skim ‘em?”

Grandpa raised the axe, chopped the goat into neat, heavy pieces. Each swing landed square on the joint, blood splattering across his cheeks—he didn’t even blink.

“Get the mutton in the pot. It’s coming—I can smell it. Like mud and something rotting.”

Uncle Jake fumbled the meat into the pot, nearly dropping it in his rush.

Grandma wrinkled her nose. “How long’s it gotta cook?”

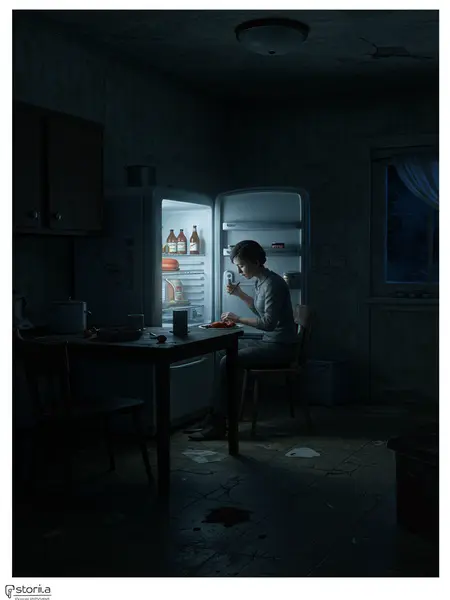

Grandpa squinted, then disappeared into the storage room. He came out with eighteen white emergency candles—the kind we used for tornadoes—and set them on the kitchen table, three rows of six. He lit each one with a wooden match.

“Cook it till these burn out,” he muttered.

Right then—tap tap. Twice, heavy and slow, like knuckles on wood.

I looked up and saw an old woman standing at the gate.

She was all bones and sagging skin, face so pale she looked dipped in flour, eyes shining weird in the porch light. Her dress was faded, flowers wilted on yellowed cotton—looked like something out of an old yearbook.

Uncle Jake nearly fainted, ducking behind Grandpa. “It’s here. It’s here...”

Grandpa’s voice was steady. “Don’t panic. Give her the chicken first. The mutton waits for the candles. Y’all hear me? This matters.”

The old woman floated into the yard, hunched and slow, feet not quite touching down right—like she was walking tiptoe, but each step thudded like a heel.

She stared at Uncle Jake and her voice cut cold. “Young man, I’ve been waiting in this town for my boy longer than you’ve been alive. Stood at that busted bus stop every day, hoping he’d come home. If I hadn’t seen you tonight, I might’ve just faded away.”

She grinned wide, showing a mouth full of too-white, too-many teeth—double rows, sharp as a dog’s.

Uncle Jake’s knees buckled, and he nearly dropped. Grandma caught his elbow, holding him up.

The old woman’s smile stretched impossibly wide. She shuffled closer, stopping three feet from Grandpa. “Young man, I haven’t eaten in decades. My belly’s so empty it hurts. Give me something to eat. Just a little—I’m not greedy.”

Her skin looked thin as wax, veins dark under the porch light. Her eyes caught the porch light, shining green and glassy, like a raccoon in the road—only meaner.

A living ghost. The thing parents warned us about, the reason nobody ever dared step outside after dark, not even on New Year’s Eve.