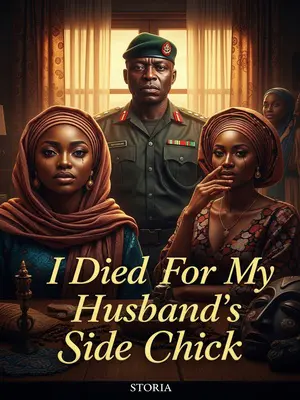

Chapter 1: The Day I Died Twice

I spent my whole life guarding the widow’s honour arch that the Oba himself had personally bestowed on me.

In those days, neighbours would hail me as Iyawo Alanu, the patient widow, and mothers pointed me out as a shining example. That arch stood grand at the Okoye compound’s entrance, painted red and gold, catching the sun. Every Sallah or New Yam Festival, elders would nod as they passed. No dust ever dared rest on its pillars; I swept it myself, even when my bones complained with pain.

It wasn’t until my deathbed that the true betrayal showed itself—my husband was alive all along.

The room thick with camphor, palm oil lamps, and the lingering smoke of Father Matthew’s final blessing. My mind was a fog of pain and regret. I heard the shuffle of women in wrappers and headties, their voices hushed as the house fell into that strange, respectful silence that comes before the last breath.

In my final moments, I heard my mother-in-law quietly instruct the housegirl:

“Wura is gone. Go and send a message to the young master—tell him to bring my good grandson and daughter-in-law back to the compound in a few days.”

Her voice cut sharp, not a drop of real grief inside. The housegirl, small and quick-footed, nodded and waka through the corridor, her slippers slapping soft-soft on the cement floor.

I struggled, tried to rise and demand the meaning of this, but still, I died with bitterness thick in my chest.

My spirit wrestled against darkness, reaching for words that refused to come. The pain pressed down, heavy as a curse, denying me peace.

When I opened my eyes again, it was the very day the news of my husband’s death arrived.

---

1

Everybody in Makurdi knows me as a model of virtue and chastity.

They called me "Iyawo Okoye wey sabi," the one who endures for her family. Children would stop their amebo, pointing as I passed, their mothers whispering, "See that one—her spirit no dey shake, even for trouble."

All because, after my husband died, I remained a widow for ten years.

In the eighth year of my widowhood, the Oba himself issued a royal proclamation, granting me a widow’s arch—a decorated gate to honour a woman’s faithfulness to her late husband.

My heart beat proud but heavy the day palace drummers marched to our gate, talking drums echoing as the Oba’s messenger called my praise names. For one brief moment, my suffering shone gold in my people’s eyes, but I alone knew the true price.

For a while, people would say: “If you want to marry, marry a daughter of the Nwachukwu family.”

Mothers would nod towards me and say, "You go learn from Wura. That one, her hands clean. She get respect." But behind their praise, some eyed me with envy and suspicion, as if my suffering gave me power over them.

But people only saw my glory from outside; nobody knew the suffering behind it.

Inside my room, away from watching eyes, I would bite my wrapper and cry into the night, missing my husband’s voice, even his footsteps on the veranda. The ache was my constant companion, quiet but stubborn.

For ten years, I carried the whole Okoye family on my shoulders, showing respect to my mother-in-law above, and caring for my husband’s younger brother below.

My back bent from bowing and standing at her beck and call. I cooked soup for Mama, fetched medicine from the chemist, and always kept small gifts for Obinna, so he wouldn’t feel the absence of his elder brother too deeply.

Outside, I managed the family’s market stalls; inside, I handled all household matters.

I would rise before cock crow, my feet dusty with red earth, greeting traders at our pepper stall. By evening, I’d return to settle quarrels between maids and fix every household wahala before dinner.

Because of all this, I fell seriously ill before I even reached thirty.

By the time my mates were still dancing at weddings, my face had grown thin, body too weak for bata. My hands trembled lifting the pestle, my laughter a whisper instead of real joy.

By my sickbed, my mother-in-law held my hand tightly, eyes brimming with tears:

“Good child, you can rest now. Your younger brother-in-law is working in the local government office. Don’t worry about Mother again.”

She dabbed her eyes with her wrapper, voice just quivering enough to look convincing. The scent of menthol and hot water filled my nostrils as she squeezed my palm.

I nodded, too tired to speak, then coughed up blood.

The taste of iron lingered on my tongue, my throat burning. The housegirl, Wura, rushed for another clean towel, but it did nothing to stop the pain.

My eyes landed on Obinna, standing behind my mother-in-law. “Little uncle, your brother left us too soon. From now on, it’s your duty to take care of Mother.”

My voice cracked, and for a moment, I saw the boy’s lips tremble, as if he too felt the weight I had carried for so long.

Obinna frowned deeply and stepped forward as if he wanted to say something, but my mother-in-law silently blocked him.

With one sharp look from Mama, Obinna bit his tongue. Family hierarchy dey strong pass cement.

I couldn’t hold on any longer and fell back onto the bed.

The pounding in my head faded to a dull throb. My body loose like after malaria, spirit floating small-small.

As I closed my eyes, a single tear rolled down my cheek.

I felt the salt sting my skin, and in that moment, a prayer escaped my lips, silent and desperate: "Olodumare, see me o."

In my last moments, I heard my mother-in-law whisper to the housegirl:

“Wura is gone. Go and send a message to Chijioke—tell him to bring my good grandson and daughter-in-law back to the compound in a few days.”

The words drifted through my hazy mind like a curse, not a comfort. The housegirl’s hurried footsteps faded away, leaving only the sound of my own laboured breathing.

“After being away for so many years, they can finally come home.”

The joy in her voice sounded sharp, almost greedy, and I realized I had never truly been family to her.

Chijioke—that’s my husband’s name, the same husband everyone said died years ago.

A cold shiver ran through my dying body. My heart dey beat kpokpo for chest—fear no let me breathe.

In that moment, questions filled my mind.

I could feel my thoughts swirling, memories and doubts rising like smoke from a dying fire. How could it be? Was I a fool for all these years?

I tried with all my strength to get up and demand answers, but I still died with bitterness in my heart.

The darkness closed over me, my body stiff with grief that would not be soothed, not even in death.

Tonight, I will show them that a widow’s patience has limits.