Chapter 2: A King Awakes with Old Blood

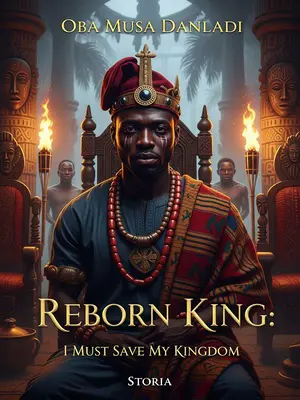

Sarki year, eleventh month. Ifedike’s spirit waka for nine hundred years before e land for King Musa’s body. For that moment, the hot blood of Ifedike burn Musa soul comot, and na so Ifedike wake up from long sleep for Uyo City.

The night air in Uyo City was thick with dust and secrets. As Ifedike’s spirit slid into the body of King Musa, he felt the weight of centuries pressing down on him, memories overlapping—ancient drums, chants at midnight, and the echo of elders’ voices reciting lineage under the moon. It was as if time itself had looped, bringing old debts and old strength back to life.

Musa:

He no even notice if he don chase any bad person comot; Ifedike just wake and the thing wey he see nearly blind am:

Musa’s mind scrambled to make sense of the new world behind his eyelids, yet his soul tingled with a power he never knew before. He sat up, eyes darting as if expecting to see ancestral masquerades appear from the corners.

Everywhere—agate and crystal, lions and eagles wey dem carve. For front, on top crystal table, golden basins full of charcoal from palm kernel and coconut shells, all dey burn well. Plenty curtains and screens wey dem weave from guinea fowl feathers.

The hall no be ordinary king house; everywhere shine like film. Dem carve lion with fangs so real e resemble the ones dem dey use for Egungun festival. The golden basins dey glow with the steady, soft fire of palm kernel charcoal, and the coconut scent mingle with the cool air, creating a perfume wey be like say person dey inside old Ibadan herbalist house, where leaf and incense dey mix for air. Curtains of guinea fowl feathers, with patterns wey resemble Nsibidi symbols, sway gently, casting moving shadows on the tiled floor.

Even flowers and plants dey inside the hall—fine like cloud, bright, all of them dey show themselves—Ifedike no sabi any of them.

He spotted ferns and wild orchids, arranged with a care that suggested a powerful hand. But the leaves shimmered with a colour no be from his time—maybe na from some ancient forest, or na just rich people get this kind flower.

But the scent wey dey everywhere pure and fresh, no get any smoke or fire smell at all.

Ifedike breathe in, expecting smoke to choke am, but instead, fresh air fill him chest, scented with lemongrass and something like garden egg. He wonder if na the work of palace herbalist or some sacred incense dem burn before sunrise.

Ifedike look up. Outside, harmattan wind dey blow cold, frost and dust just cover everywhere. E dry crack for lip, enter nose, make even royal guards dey sneeze.

He could hear the whistling sound of the wind, see dust swirling by the window, leaving a white, powdery film on every exposed surface. He hug himself small, remembering how the harmattan go slice through person wrapper for Okpoko.

Ifedike confuse. Which kind place be this? For this kind cold, people still dey live like this—abi after death, na so person dey become ancestor, enter the spirit river for Orun, climb reach the nine heavens?

He scanned the shadows, almost expecting to see his grandmother’s spirit, arms folded, waiting to scold him for unfinished chores. Maybe na the place where ancestors gather to talk, he wondered, or maybe na just one elaborate dream.

But where Okonkwo? Okonkwo suppose dey here too.

He strained his ears, hoping for the rumbling laugh of Okonkwo, his childhood friend and rival, but only the low crackle of charcoal and the distant horn of a night driver drifted in. E pain am small, say spirit world still dey lonely.

Footsteps start. Ifedike quickly come back to himself.

He heard the soft slap of slippers on marble—palace slippers, not village sandals. The footsteps steady, respectful, like those of a steward wey sabi say king fit vex anytime.

One attendant waka come, head down, talk say, “Your Majesty, Chief Auwalu send message—the raiders don enter the city. If Your Majesty no too sick, abeg, move from Royal Hall as soon as possible.”

The attendant’s voice shook slightly, but his head remained bowed in the respectful posture taught by palace matrons since childhood. Even his accent betrayed the old Riverine roots, every syllable careful, the way servants talk to avoid wahala. He carried the message with the urgency of someone who had seen blood on the sand before dawn.

Ifedike:

Wetin be ‘Your Majesty’? And which kind ‘move’ be this?

He repeated the words in his mind, rolling them over his tongue, almost laughing at the absurdity. Only yesterday, he was 'Uncle Ife' to Mama Chidinma, now na 'Your Majesty.' Even the way dem say 'move' get double meaning—like say person dey dodge bullet or just shift for bus stop.

Plenty thoughts dey run for him head, but Ifedike face no show anything. As person wey don see life, he just nod: “No wahala, you fit go.”

He kept his face tight, lips pressed together, just like when he used to negotiate for land with stubborn relatives. He nodded with the calm of a man who don bury all his worries beneath agbada.

As the attendant comot, Ifedike eye dey waka everywhere for Royal Hall, dey find any writing.

He moved quietly, glancing around, the way a market woman dey scan for police before setting up wares. The Royal Hall looked less intimidating when he imagined it as an old meeting house in Okpoko, where the elders would argue for hours over who owed who tubers of yam.

First thing wey he see na the table for front, full of petitions from different places. Plenty of the place names confuse Ifedike, but e still help am guess who he be now—he still be king.

He ran his hand over the heavy paper, tracing out the unfamiliar names—Gashua, Obudu, Bida—each one sounding like a riddle from his youth. If he was king now, then this was no longer a dream but a new burden sewn with invisible thread.

But as Ifedike check the ones wey talk about tax and grain from different areas, na so him eye nearly comot for socket:

His heart raced as he scanned the numbers, mouthing the figures under his breath like a market trader counting change after a big sale. The sheer wealth detailed there—he felt as if he stumbled into CBN vault. This na money wey pass all the politicians for Abuja pocket.

Kai! For all the sixty-something years wey he live before, he never see this kind money before, even during war.

He remembered counting coins after the Biafra war, stacking pennies to buy salt and kerosene. This level of riches—na only politicians dey see am for Abuja, he thought. His lips almost whistled in awe.

But the next one talk about peace talk with the raiders—give them land, pay tribute: every year, twenty-five thousand bags of cowries and twenty-five thousand rolls of fine cloth.

His palm went cold. He could almost feel the weight of each cowry shell in his hand, see the women on market days, counting and recounting, cursing the tax collectors. The price of peace, written in the sweat of farmers and the tears of widows. Women go curse, children go cry, but council elders go still chop.

Ifedike freeze. He dig through the petitions, finally see the exchange rate for cowries to naira for this era—at least two thousand cowries for one naira.

He tried to do the math in his head, the way old men do in front of lottery kiosks. The numbers no dey add up—na real robbery.

That one na fifty million cowries, plus twenty-five thousand rolls of cloth—pass all the tax wey Palm Grove dey collect in one year.

He shook his head, muttering a soft 'Chai!' under his breath. He imagined the tailors working through rainy season and harmattan, backs bent, eyes red, all for tribute wey no go end.

Ifedike take deep breath. The air still dey fresh and pure. Him eyelid shake. If person dey there, dem for see say fire just flash for Ifedike eye.

He let the anger rise, steadying himself the way his father once did before confronting tax masters. He inhaled, filling his chest with the sharp, cold air, readying for the fight ahead.

He suddenly wan draw machete, run somebody down.

He gripped the table edge, fingers white with tension, the memory of old battles flickering behind his eyes. A voice in his head shouted, 'Na today wahala start!'

After he get the idea of wetin dey happen, Ifedike look around the Royal Hall again, this time he no see any spirit river of Orun. All those crystals, agates, orchids—for him eye, dem all turn to blood.

His vision blurred, red streaks running across the surfaces. Every glittering stone now looked like a pool of sacrifice, the room thick with the suffering of forgotten people.

For sky wey blood dey rain, Ifedike begin see the music and enjoyment for late Makurdi, the waste wey King Eze and King Bala do.

He remembered the wild celebrations in Makurdi, the drumming that lasted till dawn, and the reckless spending of leaders who forgot those they served. The echo of those drums now sounded like war drums.

And behind that—na the people wey die for Okpoko, the poor farmers for Otukpo wey go work from morning till night, but only fit chop meat two times a year, people wey disaster don finish, yellow face, thin body, carry their family dey waka from place to place.

He saw their faces—thin, hungry, eyes hollow with tired hope—children with swollen bellies from kwashiorkor, mothers carrying babies on tired backs, fathers trudging behind, all searching for small mercy on red earth roads.

This place no be immortal land wey cold or heat no dey reach. Every inch here na the sweat and blood of the people, na the suffering of ordinary man.

He gritted his teeth, heart pounding. Even in palace of glass and gold, hunger still dey knock door. The cost of every luxury weighed on him like chains of iron.

Ifedike exhale, look up. Sixty years of hardship from his former life dey shine for his eye, and that old hero spirit just wake up again inside am.

He stood taller, back straight, the memories of Okpoko and Makurdi stirring strength into his bones. This was not a time to fear.

To die and come back—whether na destiny or ancestors wey dey do am—since I don come, I no go let Palm Grove land spoil for these kind people hand.

He nodded once, quietly invoking his ancestors, the old warrior creed whispering in his veins: 'As long as I get life, I no go let evil prevail.'

That day, Ifedike sit down dey read all the petitions and drafts for Royal Hall, dey piece together wetin dey happen: north and south dey fight, Palm Grove and raiders dey drag each other for blood, but both still dey do peace talk.

He settled into the heavy armchair, reading late into the night, his fingers tracing the inked words. He marked the names of allies and enemies, committing them to memory the way market traders remember who owe them debt.

To talk true, no be negotiation, na Palm Grove dey surrender and dey serve the raiders.

He frowned, seeing the subtle insult woven through the documents. Palm Grove was being humbled—no be peaceful talk, na defeat wearing fine clothes.

No be only to give land and pay money, the raiders still ask for two strange things: first, make dem no change any big chief; second, make dem kill Chief Bamidele.

His heart skipped. The demand for Bamidele’s head was the true price—he knew that trick: divide the loyal, remove the stubborn, leave only those who go bend like plantain leaf in the rain.

Ifedike eyelid shake. This one clear—na bad belle elders dey join hand with enemy just to get power, but the brave chief wey dey make raiders fear, dey suffer for prison.

He spat softly on the marble floor, a gesture of disgust he’d learnt from his grandfather. Power dey sweet, but betrayal dey bitter pass bitterleaf soup.

So wetin the last king dey do since?

He shook his head, thinking of past kings whose pride and laziness scattered their people like dry leaves in dry season.

As he check deeper, Ifedike find the name wey he dey use now for the official papers:

He paused, running his thumb over the royal seal, the ink still smelling faintly of camphor.

Musa.

His new name weighed heavy, but also full of new meaning. He tested the sound in his mouth, letting it blend with the old Ifedike—the man he had been, and the king he must become.

No wahala, Musa don die. From today, this world get only Musa Ifedike.

He nodded, setting his jaw with the stubbornness of a true Okpoko son. Musa Ifedike—twice born, ready for war.

Musa Ifedike take deep breath, call for keke, order make dem carry am go palace.

He shouted for the palace guards, his voice now thunderous. 'Oya, call keke! No time!' His command rang with a new authority, surprising even himself.

Tonight, Musa Ifedike go show say even spirit fit fight for tomorrow.