Chapter 1: The Night the Lake Returned Her

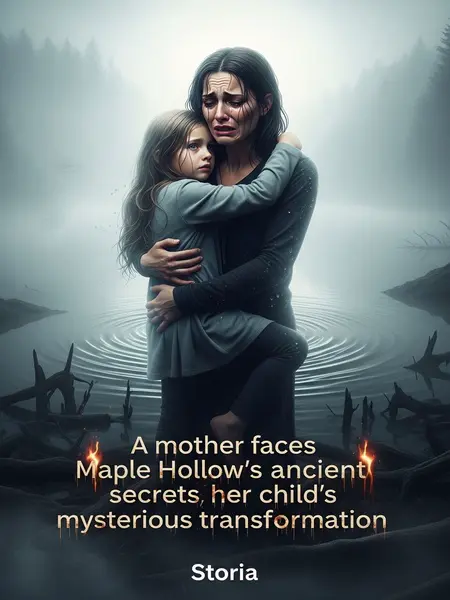

My eight-year-old daughter vanished into the lake, and after that, nothing in the world felt real. The words replayed in my mind every night, haunting me like a fever I couldn’t sweat out. There’s a kind of silence after a child disappears—a silence that seeps into the walls, settles deep into the bones of a house. Everything went still. I’d sit by her empty bed, tracing the dent in her pillow, straining for any sound—a giggle, a splash from the bathroom, a thump on the floor. Anything. But all I ever got was the thick, smothering hush of loss, so heavy I could barely breathe.

Two weeks passed. Each day stretched longer than the last, the ache settling in my chest like a stone. Then, out of nowhere, she came home. I was standing in the kitchen when the door creaked open, and there she was—dripping wet, her belly swollen in a way that made my heart stop. For a second, I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. Was this really happening? Was I awake? I just stared, the dread building like a storm in my gut.

I’ll never forget the way she looked when she stepped onto our porch—water streaming down her arms, hair tangled up with lake grass, her eyes wide and empty. The porch light buzzed and flickered as she crossed the threshold, leaving a dark puddle in her wake. For a heartbeat, I thought maybe my mind was just playing tricks on me, that this was some cruel mirage conjured up to soothe the pain. But she was real, and her shirt clung to her skin, stretched tight over a belly that didn’t belong on a child. My knees nearly buckled.

That night, she gave birth to a mess of fish-creatures, all knotted up with lake weeds and slime.

I was right there, holding her hand, my heart thudding so loud I was sure it would burst right through my ribs. The whole room filled with the reek of algae and something sharp and metallic, like blood. I tried to pray, but my mouth just went dry. The only sound was water dripping from her hair, and the wet, squirming slap of whatever was coming out of her. It was worse than any nightmare, because I was wide awake and couldn’t look away.

Their faces almost looked human—almost—but their backs were bristling with fins.

Each one writhed and gasped, their mouths working open and shut in silent, desperate screams. There was something in their eyes, too—something that seemed to see me, to know me, like they recognized I was their grandmother. I wanted to run, to scream, but I was frozen to the spot. My legs wouldn’t budge.

Five tiny yellow eyes were bunched together in rows, and the brownish fish scales on their bodies gave off a sharp, raw stench that made my stomach turn.

The smell hit me like a punch—like stepping into a bait shop in the middle of July, only so much worse. It crawled up my nose and sat heavy in the back of my throat, making me gag. The scales shimmered under the lamp, and all those blinking yellow eyes just stared at me, waiting for something I couldn’t give.

The old fortune-teller said, "That’s your daughter’s child with a water spirit. She carries the scent of death."

Everyone in Maple Hollow has a story about Mrs. Wilkins. That morning, she shuffled up to our porch with her battered tarot deck and a jar of river stones, sniffing the air like a hound, crossing herself, muttering about things best left at the bottom of the lake. Folks in town listened to her even if they pretended not to. I wanted to yell at her to get off my porch, but my throat was tight and the words wouldn’t come. She said the scent of death lingered—heavy as the morning mist rolling off the lake—and I couldn’t shake it.

Our family lives in Maple Hollow, a small mountain town with the woods pressed up behind us and a handful of big lakes scattered all around.

Maple Hollow isn’t on most maps. If you can even find it, you have to drive past three empty gas stations and a boarded-up diner just to get here. The air always smells like pine needles and damp earth, and the lakes are so cold they steal your breath even in July. Our house sits at the very edge of town, the backyard sloping down toward the biggest lake. Sometimes, if the wind’s right, you can hear the loons calling at dusk, their cries echoing through the trees and giving you goosebumps.

The houses are all stone and clapboard, scattered between the lakes, keeping each body of water just a little apart from the next.

It’s the kind of town where every house has its own story—and most of those stories aren’t happy. The stones in our walls were hauled up from the riverbed by my granddad. The clapboard’s been painted over so many times the color’s never quite the same from year to year. Folks say the houses keep the lakes apart, but I always figured it was the lakes that kept us apart—from each other, and from the world on the other side of the ridge. Sometimes I’d stare out at the water and feel like I was living on an island.

Most of the men work out of state, so the only ones left are the elderly, the frail, the women, and the kids.

Every spring, the men pack their duffel bags and pile into battered pickups, headed north to the oil fields or the canneries. We stand on the porch and wave, pretending it’s just another season, but every year, fewer of them come back. The rest of us—the grandmas, the moms, the kids—keep the town running. We trade casseroles and gossip, look out for each other’s kids, and wait for the phone to ring. I remember the first year my husband left, how I kept checking the mailbox, hoping for a letter that never came.

If something dangerous happens, it’s tough to get help in time. Truth is, you’re on your own out here.

Ambulances are at least an hour away, if they bother coming at all. The sheriff’s office is two towns over, and the volunteer fire department is mostly teenagers and old-timers. When there’s trouble, we handle it ourselves. That’s just the way it is in Maple Hollow.

That’s why the kids here learn to swim early. Out here, you have to. My daughter, Lila Mae, is one of the best swimmers around.

By the time she turned five, Lila Mae could swim the length of the lake and back without stopping. She’d splash around with the other kids until their lips turned blue, then race them to the dock for bragging rights. Folks would shake their heads and say she was half fish herself. I’d watch from the shore, hands clenched so tight my knuckles hurt, praying she’d pop up laughing.

As her mom, I’m actually the worst swimmer in the county.

It’s a running joke at the summer picnic—how I nearly drowned in the shallow end of the town pool. I can barely dog-paddle, and even then, only if someone’s watching me like a hawk. Lila Mae used to tease me, promising she’d teach me to float someday. I’d always laugh and say, "Sure, kiddo," but deep down, I knew I’d never learn. I still get nervous just wading in.

That morning, before she disappeared, Lila Mae told me, "Mom, I’m going to play with Shadow."

She had her backpack slung over one shoulder, hair in crooked pigtails, and a grin that could melt stone. Shadow, I thought—wasn’t that the neighbor’s dog? I barely looked up from the sink, too busy scrubbing the breakfast dishes. "Alright, honey," I called, "just don’t go too far."

I remembered my sister’s house had a little black dog, gentle and sweet, so I told her, "Don’t be out too late."

Marlene’s dog, Buddy, was the kind of mutt every kid in town loved—always wagging, never biting. I figured Lila Mae would be safe over there. I watched her skip down the gravel path, the morning sun glinting off the lake, and told myself not to worry. What could go wrong in a town like this?

Lila Mae played all afternoon. At first, I didn’t think anything was wrong. She got along with the other kids, and sometimes other families would invite her to stay for dinner.

The neighborhood kids ran wild, darting in and out of each other’s yards, chasing fireflies and playing hide-and-seek in the woods behind the houses. Sometimes Lila Mae would come home with mud on her knees, pockets full of rocks, and wild stories about secret forts. I never minded—Maple Hollow was the kind of place where you let your kids roam, at least until the sun dipped behind the trees.

It wasn’t until nine at night that someone pounded on the door: "Maggie, your Lila Mae drowned!"

The knock was frantic, rattling the glass in its frame. I swung the door open and found Mr. Perkins, his face white as a sheet, raincoat soaked through. He barely got the words out before I was scrambling for my coat, heart jackhammering in my chest. The world spun sideways, and all I could think was, this can’t be real—she’s just a kid, she’s just playing, she’ll come home any minute. Please, God, let her come home.

The lake where Lila Mae drowned is the biggest in town, so deep it looks pitch black from far away. Folks say it’s bottomless.

It’s called Blackwater Lake for a reason. The water’s so dark you can’t see your own reflection. Locals say it’s got no bottom, that it connects to all the other lakes underground. On clear nights, the moonlight barely touches the surface. I’d always warned Lila Mae to stay away from the far end, where the water gets cold and strange things move beneath. There are stories—always stories.

There’s only one streetlight for blocks. People brought flashlights, some used their truck headlights. A few teenage boys dove in to search for Lila Mae.

The whole town gathered at the water’s edge, voices hushed, flashlights bobbing like fireflies. Billy, Mike, and Jamie stripped down to their shorts and waded in, teeth chattering. The older women prayed, and someone passed around a flask. I stood on the shore, clutching my coat, legs shaking so hard I thought I’d collapse.

My legs buckled, but I forced myself to the lake’s edge, desperate.

Every step felt like I was moving through wet cement. My knees wanted to give out, but I kept going, driven by something raw and frantic. The mud sucked at my shoes, cold water lapping at my ankles. I shouted Lila Mae’s name until my throat burned, but all I heard was the wind and the water.

Nothing of Lila Mae’s was left on the shore. The neighbors said, "The widow found her first."

The only thing left was a single, muddy footprint pressed into the sand. The others crowded around the widow, old Mrs. Carter, who was wringing her hands and staring at the water like she’d seen a ghost. Her face was drawn, eyes darting back and forth.

The widow was wringing out her clothes, face pale with fear. "I saw Lila Mae swimming, not coming up for a long time. When I got closer, I saw her being dragged under by something dark. I jumped in, but found nothing."

Her voice shook so bad I could barely understand her. She hugged herself, shivering, soaked to the skin. Folks whispered about what she’d seen, but nobody wanted to believe it. I stared at her, hoping for some sign this was a mistake—a trick of the light, a bad dream. But her haunted eyes told me otherwise.

The boys who’d gone in came up then, all shaking their heads. No luck.

They stood shivering on the bank, mud smeared up their arms, hair plastered to their foreheads. Jamie wouldn’t meet my eyes. Billy kept glancing at the lake, like he was waiting for something to surface. I wanted to scream at them to try again, but I knew it was useless.

I broke down in tears. Lila Mae was only eight, sweet and strong—a better swimmer than any of them. How could she have drowned?

I dropped to my knees, sobbing into my hands. Someone tried to help me up, but I couldn’t move. My little girl—my fearless, bright Lila Mae—gone, just like that. It made no sense. She was the best swimmer in town, could hold her breath longer than the boys. How could she just vanish?

I blurted out, pointing at the widow, "You’re lying!"

The words spilled out before I could stop them. The crowd went quiet, everyone looking at me and then at her. I remembered how the widow’s mind had gotten a little strange since her husband died—how she’d claimed to see things, to hear voices from the lake. Maybe she was confused, or maybe she’d seen something nobody else wanted to believe.

Her husband had died mysteriously years ago; her mind had never been right since. Maybe she was just mistaken.

People always whispered about her—how she wandered the woods at night, how she talked to shadows. Maybe she’d just imagined it all. Maybe Lila Mae had run off somewhere else. I clung to that hope, even as dread pressed in on all sides.

Someone behind me reached down to help—it was my sister, Marlene.

Marlene’s hands were warm and steady, grounding me. She crouched beside me, her voice gentle but firm. "Come on, Maggie," she said, "let’s get you home."

"Marlene!" I grabbed her sleeve, desperate, clutching it like it was the last thing keeping me afloat. "Lila Mae said she was going to play with your dog Shadow. Where is he?"

I held on, refusing to let go. Marlene’s eyes widened, confusion all over her face. For a moment, I thought maybe she’d remember something I’d missed.

My sister looked startled. "Shadow? My dog’s name is Buddy. Lila Mae knows that."

She shook her head, eyebrows knitting together. "We’ve never had a dog named Shadow. Buddy’s the only one."

I was stunned, my face twisted in confusion. "What do you mean? Then who was the Shadow Lila Mae mentioned?"

I racked my brain, trying to remember every conversation, every bedtime story. Had Lila Mae made up an imaginary friend? Or was there another dog I didn’t know about? My thoughts spun in circles.

I looked back at the neighbors by the lake—none of them had ever heard of any Shadow.

They all shook their heads, murmuring to each other. Someone suggested maybe it was a stray, or a nickname for one of the other dogs. But nobody had ever heard of a Shadow.

Maybe I was out of it. The widow said, voice shaking, "It was too dark. Maybe I just saw wrong."

She backed away, twisting her hands, her eyes flicking to the water. I wanted to believe her, to believe this was all some terrible mistake. But deep down, I knew something was off.

The crowd drifted away, leaving just the wind and my muffled sobs by the lake.

One by one, they slipped away, flashlights bobbing into the dark. The lake went quiet again, except for the gentle slap of water on the shore. I stayed long after everyone else, listening for a voice that never came.

The town council president came by the next morning, urging me to hold a memorial for Lila Mae.

He showed up on my porch, hat in hand, trying his best to look sympathetic. "It’s what folks do, Maggie," he said. "It’ll help you heal." I nodded along, but the idea of a funeral with no body made me want to throw up.

My sister said I should call my husband, who was working out of state, and tell him about Lila Mae.

Marlene sat with me at the kitchen table, her hands clasped tight. "You should tell him," she said, her voice soft but insistent. "He deserves to know." I just stared at the phone, unable to pick it up. How do you tell a man his daughter is gone when you haven’t even seen her body?

I refused both. Deep down, I figured if I didn’t see Lila Mae’s body, I couldn’t hold a funeral. I just couldn’t.