Chapter 1: The Mountain’s Invitation

In three days, I guided four women up the mountain trails—each with her own secrets, each leaving a mark.

Sometimes, when the wind changes, you can smell woodsmoke from the last tea stall below, or hear the distant clang of temple bells drifting up the valley. Up in the hills, especially near those dizzying cliffs and dangerous drops, there’s always someone waiting to cross that invisible line—again and again, as if every leap is a new birth or a final end. Sometimes, the wind carries their laughter; sometimes, only silence remains.

He once told me, "There are still too many joys in this world that haven’t been tasted."

I remember that evening so clearly—his voice was soft, but it carried something heavy, like the last glowing coal in a dying chulha. I couldn’t tell if he meant joys or sins, but something inside me shifted.

From that day on, I felt different too—less like a regular boy from the village, more like someone who’d tasted a forbidden fruit.

That night, as the village dogs howled at the moon and the distant sound of a train echoed through the valley, I realised something had changed forever. Even the mountains seemed to look at me with new eyes; even Ma’s voice at dinner sounded far away, as if I was listening from underwater.

1

On the afternoon of Teej, I took the second woman to Uncle Nilesh.

Teej had filled the village with songs and the smell of steaming modaks, but I was out on the dusty trail, carrying a stranger’s dreams uphill. Women’s sarees in every colour—parrot green, maroon, peacock blue—flashed between the neem trees as they sang old songs, their laughter echoing down the hillside. The festive bangles jingling on women’s wrists faded behind me as I led Meera into the forest.

Her name was Meera. She had short hair, sun-kissed skin, and wore a pair of oversized round glasses.

She reminded me a bit of the city schoolteachers—sharp, lively, never shy to let out a big laugh. The sunlight glinted off the gold rims of her glasses, and the breeze tossed her hair as we walked.

Unlike the woman from yesterday, she was genuinely cheerful—just like her name suggested.

She’d greet every butterfly with a gasp of delight, and every pebble on the path seemed to spark a story from her. Sometimes I wondered if she’d ever even known sorrow.

She kept firing questions at me the whole way: from Lonely Planet guides to Lucknowi chikan work, anything new left her eyes shining. "Bhaiya, you ever tried real Rajasthani ghevar? My nani swears it’s better than jalebi!" she teased, grinning. I shot back, half-teasing, half-proud, "Arrey, our hill ladoos can make your nani forget all about ghevar."

She walked as if she was dancing, light on her feet, skipping and twirling.

She’d swing her bag, spin around, then leap onto a big flat stone and call out, "See, Bhaiya! I could be a mountain goat!" I couldn’t help but smile, no matter how much I tried to act serious.

To be honest, I didn’t know why I was taking her to see Uncle Nilesh either.

I had the same question yesterday, but brushed it aside. Only by noon did I realise the woman I’d brought yesterday, Ritu, hadn’t come back.

A strange coldness crept up my spine. In our village, even city girls never stayed out after dark. Not alone.

In other words, Ritu had spent the night with Uncle Nilesh at the campsite.

No one else was there; for the past six months, that place had been Uncle Nilesh’s private paradise.

Maybe I was taking Meera over to bring Ritu back, or so I told myself.

But in my heart, I knew I was just following Didi Anya’s instructions, and who was I to say no?

My mind wandered the whole way. What should have been a two-hour trek stretched to three, because Meera’s curiosity made us stop at every turn. Only when the sun was about to set did we finally arrive.

The sun was dipping, painting the sky orange and violet. The cicadas began their evening chorus, and the air was thick with wild jasmine.

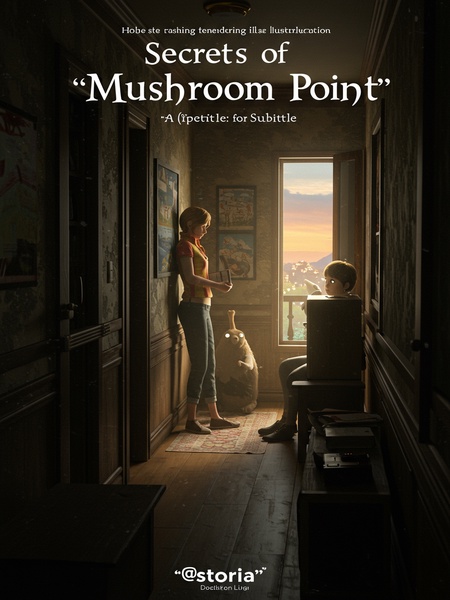

Mushroom Point—a hidden marvel in the Western Ghats.

It juts out from the hillside like a giant mushroom cap, hanging hundreds of feet above the valley, which is how it got its name.

The endless green hills open up here like a balcony, the view stretching in three directions, sunlight pouring in, ancient banyan trees and wildflowers everywhere.

It’s a place even the village elders whisper about; they say it’s older than memory, the air itself heavy with old secrets.

For an experienced trekker like Uncle Nilesh, it was the perfect campsite.

We climbed up to Mushroom Point in the glow of sunset. Uncle Nilesh was roasting fish over a campfire.

He sat cross-legged, humming an old Kishore Kumar tune, the flames casting shadows on his weathered face. A battered kettle whistled gently by the fire.

The fish was freshly caught, grilled on a hot stone with just salt and masala—better than any five-star meal.

That aroma brought back memories of monsoon nights when my father would roast river fish after a long day in the fields.

“Arrey Raju, Meera is here,” he called out.

He always used my nickname, never my full name. There was a warmth in his voice that made Meera beam, like she’d been let into a secret club.

The aroma made my stomach growl after the long walk.

The crackle of the fire mixed with Meera’s laughter, and for a moment, I felt almost happy to be there.

Uncle Nilesh looked up and smiled. “Perfect timing, come join us.”

Meera and I sat around the fire, and Uncle Nilesh handed each of us a fish.

He used his bare hands, like the old fishermen at the ghat. Meera wrinkled her nose at the bones, but took a careful bite anyway.

Rohu—the freshest you’ll ever get, though a bit bony.

Meera giggled as she picked out the bones, while I just chewed and spat them out like I’d done since childhood.

As I gnawed on the fish, Uncle Nilesh quickly counted out ten crisp notes and stuffed them into my pocket.

He did it so smoothly, it was almost like a magician’s trick.

I tried to refuse. “No, no, I can’t take your money.”

Uncle Nilesh forced the money into my pocket. “Eat first. When you’re done, help me set up a tent. I went over the hill hunting for quail today—came back empty-handed and nearly died of exhaustion.”

His tone was firm, the way elders always are in our village—no room for argument, but never harsh.

“No problem, I’ll do it right away.”

As I stood up, something struck me:

Where’s Ritu?

I looked around Mushroom Point. Even though it’s perched on a cliff, the top is a flat expanse.

The wind picked up, sending a chill through my sweat-soaked shirt. I scanned the area again, squinting as the last light faded.

She’s just a girl—she wouldn’t have gone down the hill alone, right?

There were no footsteps leading away, just the smell of campfire and the call of a distant owl. My heart started thumping harder.

My eyes landed on the yellow tent Uncle Nilesh had already pitched.

The tent stood out—a bright yellow spot against the grey rocks and green moss, like a misplaced marigold.

“Uncle, is it okay to set up the tent here?” I called out.

“A bit farther, about… ten metres away.”

His voice was casual, but didn’t say which direction. In these hills, ten metres could mean a world of difference.

Carrying the tent parts, I wandered around looking for a spot. As I passed the yellow tent, curiosity got the better of me.

My hands shook a little as I fumbled with the tent pegs, but the mountain air suddenly felt much colder.

The zipper was half open. Inside, a pair of legs was curled up.

Stockings. No shoes.

Ankles bound with iron chains.

For a moment, I thought my eyes were playing tricks on me. The chain was thick, the kind the village head uses for his bullocks during monsoon. The air inside the tent was stale, heavy with silence.

Continue the story in our mobile app.

Seamless progress sync · Free reading · Offline chapters