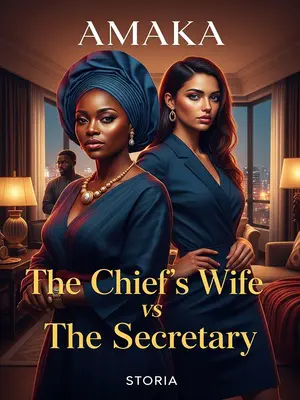

Chapter 2: The Day of Sorrow

On the day of the new queen’s installation, Chief’s Wife Amaka talk say she no want live again.

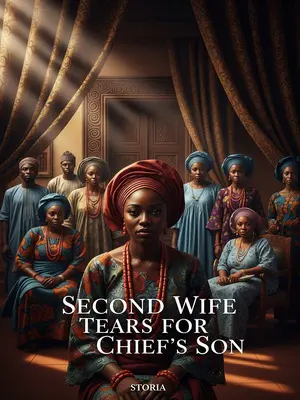

Palm Grove Estate buzzed that morning—goat meat stew aroma tangled with the smell of newly swept red earth. Drummers from the next village pounded ogene, but in the inner chambers, sadness crawled about like a lost cat. Amaka sat by her bed, wrapper loose, hair unbraided, refusing all help.

She try run hit head for wall, wan jump inside well, refuse to chop or drink—she just dey suffer herself till she no get strength again.

The servants whispered, watching from behind curtains, afraid to get too close in case the chief noticed. Her pain became everybody's business, yet no one dared approach her directly. Na so big woman dey suffer alone, even in the midst of plenty.

The chief, panic, go dey rush come her side as soon as elders’ meeting finish, hold her hand, eyes red like say he never sleep.

He would mutter prayers under his breath, sweat breaking on his forehead despite the ceiling fan. His agbada rumpled, his cap forgotten on the chair, he looked less like a powerful man, more like a lost husband.

"There are eighty servants in Palm Grove Estate. If you no chop today, I go sack ten. If you no chop tomorrow, I go sack twenty."

Everybody for hall suck breath—who wan be next to go village empty-handed? People gasped. For chief to make such a threat, you know say the matter don pass normal. The air in the hall turned heavy, every servant’s heart beating fast as palmwine drum.

As she hear am, Amaka break down begin cry.

Her cry echoed like the sound of a broken calabash, her voice stretching out the pain until even the walls seemed to sigh. Some junior maids started to cry quietly, afraid their own fate would soon follow.

One single tear drop from her fine but empty eyes—no hope again, totally broken.

That tear shone like a bead under the harsh morning light, trailing slowly down her cheek and vanishing into her wrapper.

"The thing wey pain me pass for this life be say I love you."

The hall fell silent, not even the old tortoise under the stairs dared move. Everyone knew what that meant—a kind of confession only death could explain.

With that, she just use hand comot the hot yam porridge wey I dey hold.

The tray almost crashed, but I held it steady, the smell of burnt palm oil filling the air. That single gesture said more than any insult—rejecting food in our land is like rejecting life.

"Chukwudi, no dey use other people life threaten me. You no reach."

Her voice cut through the room, clear and sharp, like machete slicing sugarcane. The chief’s face twitched, surprised she called him by his birth name in front of everyone.

The chief vex, shout "Good!" three times, then just point anyhow at one housemaid wey dey near the door.

His eyes wild, spit flying from his mouth. The servants flinched, shifting their weight from foot to foot, knowing what that kind of anger could bring.

"Drag them out. Beat them till dem die."

The words landed like heavy stones, scattering hope. Some of us held our breath, others closed their eyes and prayed under their breath. The elders pretended not to hear, but their hands trembled as they gripped their walking sticks.

When chief talk say ten, nobody go survive. The last person wey dem drag come out na Sade, the same Sade wey dey serve tea near me.

The guards didn’t even wait for orders. They grabbed Sade by the arm, ignoring her pleas, her headscarf slipping to the floor. The other maids shrank back, silent, hearts hammering inside their chests.

She dey shake like leaf, her face full with tears of fear, her voice crack as she dey beg, full of pain.

"My madam, abeg chop small. Na me, Sade, I don dey serve you since we small—abeg, save me!"

Her cry carried across the courtyard, cutting through the drums outside. Even the market women fetching water at the well paused, feeling the heaviness in the air.

"My madam, remember that time I take knife for you when I be small!"

She knelt, voice trembling. The guards yanked her up, but she clung to my wrapper, begging, calling all the old memories. Her desperation made my skin crawl.

Chief’s Wife Amaka cry even more, tears just dey rush down her pale face.

Her whole body shook, her wrapper slipping. The kind of cry that makes your chest ache to hear it, the kind you only hear from someone with nothing left to lose.

"Chief, you don happy now? You kill my closest maid, leave me all alone—you don happy? I fit die now?"

She spat the words out, bitter, broken. The elders glanced at each other, afraid to speak, for fear of becoming the next target.

The chief no talk for long.

His face became hard like carved ebony, lips pressed together. He looked away, ashamed, but pride wouldn’t let him back down.

Outside the hall, the sound of koboko dey land for people back and waist, mixed with the servants’ cry for help.

Each scream sliced through the air. The sound of cane on flesh mingled with desperate prayers, the sharp crack echoing off compound walls. Even the birds in the orange tree scattered, their wings frantic.

Even that time, them no gree give up, still dey beg chief for mercy, still dey beg the madam to save them.

Voices cracked, hands reaching out through barred gates, hope refusing to die even as blood stained the earth. I held my breath, knuckles white on the curtain pole.

Me, I just keep my head down, press my back tight against the curtain pole, my legs dey shake under my wrapper.

I felt my spirit squeeze small, wishing I could disappear into the cracks in the floor. My mind wandered, just for a second, far from the noise and violence.

That moment, I just remember one thing wey madam tell us years ago.

She talk say: "For my compound, no true servant—everybody dey equal. If you no happy, come tell me any time."

Those words haunted me—empty, maybe, or maybe she believed them once. In that moment, they felt like a lie too heavy for the room.