Chapter 2: Buried Where No One Looks

I died when I was nine.

Because I was so young, the preacher said I couldn’t have a proper grave. Some county rule, he told my grieving mother—kids who died this way weren’t allowed in the regular cemetery. So they found a patch of roadside dirt under an old oak tree, right past a faded mailbox stuffed with grocery flyers. Sun-bleached plastic flowers wilted beside my wooden marker, and the wind always picked up just as the service started.

I watched as they lowered my body in a small black casket and buried me by the roadside.

The casket looked too tiny, like something for a doll. The preacher muttered words I didn’t understand, his hand trembling as he scattered dirt over the lid.

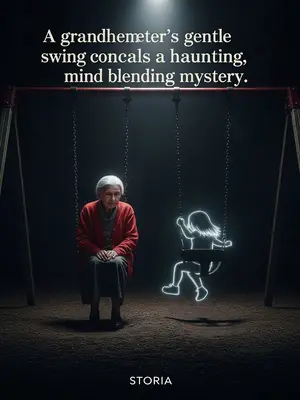

Mom came to cry at my grave so many times.

She’d drive up in her old blue Toyota, headlights flickering, parking just feet from the ditch. Sometimes she’d bring a bouquet from Kroger, sometimes just herself and a thermos of coffee, hands shaking as she poured some out for me.

She wept so hard her whole body shook with sobs.

Her sobs would carry on the wind, raw and unfiltered. Cars slowed as they passed, but nobody ever stopped.

She kept apologizing, even slapping her own face, saying, “Why wasn’t it me who died?”

She’d say it over and over, her voice rough. She’d press her palms to her cheeks, leaving red marks that wouldn’t fade until the next day.

Every time, I’d hold her hand and say:

“Mom, I don’t blame you. Please don’t cry anymore.”

I’d squeeze her fingers, willing her to feel me. I’d try to brush away her tears, just like she used to do for me when I scraped my knee. My hand passed through hers, cold and useless. It felt like shouting into a hurricane—nothing I did could reach her.

But Mom couldn’t feel me, and she couldn’t hear my voice.

My words drifted into the empty air, disappearing like fog in sunlight.

Dad came a few times, too.

He was always jumpy, glancing over his shoulder like he was afraid someone would see him. He’d park across the road and walk over, hands stuffed deep in his pockets.

He’d bring dolls and cupcakes, sit in front of my little grave, stroke it like he used to pat my head, and say:

“Ellie, honey, I’m so sorry. Daddy messed up real bad.”

His voice would catch on my name, as if the word itself hurt to say.

“These are the birthday presents I owe you for your ninth year.”

He’d set out store-bought cupcakes with waxy frosting, a Barbie with tangled hair—lining them up on the grass like I could still reach for them.

“Daddy… still hasn’t taken you to the amusement park…”

He said it like a promise he never kept, voice wobbling as he stared at the ground.

As he spoke, Dad started to cry.

He’d wipe his nose with the back of his hand, sniffling, shoulders shaking like he was trying not to fall apart. Sometimes he’d look up at the sky as if hoping I’d peek down from a cloud.

She hovered behind him, arms crossed, muttering, "Don’t be so sad, Mark. Ellie’s in a better place now. If you want to blame someone, blame her mom—she started all this."

Sometimes my voice came out shaky, a whisper in the breeze. No one ever heard. But I said it anyway: “But Miss Janine, you were the one who broke up our family first.”

Dad choked up and asked, “Ellie, in the next life, will you be Daddy’s daughter again?”

His words made the sky feel heavy, the clouds pressing down on the roadside. I wanted to answer him—wanted to say yes, or maybe, or anything—but I just looked away.

I hesitated and didn’t answer.

The wind picked up, scattering flower petals across the grass. I watched them tumble and disappear into the ditch.

Lots of people came to my grave: classmates, teachers, my best friends.

They came in cars rattling down the dirt road, hugging each other, bringing plastic-wrapped bouquets and hand-drawn cards.

They all brought food I liked.

PB&J sandwiches, gummy bears, even bags of cheese puffs I used to sneak in my backpack. Someone left my favorite comic book, pages dog-eared, the cover creased just like I left it.

They all cried.

Even the teachers who used to scold me for talking in class. My best friend Rachel left a pink bracelet by the grave, tears streaming down her cheeks as she whispered, “Miss you, El.”

I wanted to comfort them, to tell them not to be sad anymore.

I hovered close, tried to lay a hand on their backs. I willed myself to smile, to tell them I was okay, that it didn’t hurt anymore.

But no one could see me, and no one could feel me.

My world was made of silence. I drifted, watching life go on without me.