Chapter 2: Buried by the Roadside

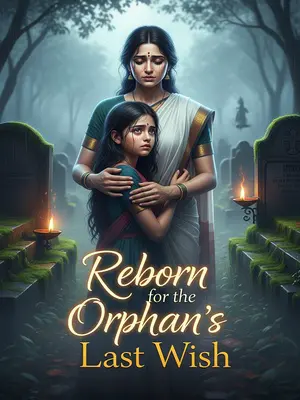

I died when I was nine, just after the monsoon ended and the world was thick with the scent of wet earth. My days had been full of pithoo games in the street and dreams of birthday parties with balloons tied to the gate.

Because I was so young, the pandits said I couldn’t have a proper cremation at the ghat. It wasn’t allowed.

Baba in his saffron dhoti shook his head gravely, muttering about the rules of the riverbank. No one below a certain age, he said. For a child, the fire was not auspicious. Amma wept at his feet, but tradition would not bend.

I watched as they put my body in a small wooden box and buried me by the dusty roadside. There wasn’t even a proper shroud—just a faded bedsheet. The grave was dug in haste, the earth thrown back with callused hands. Amma broke her bangles at the spot, her wails piercing the morning air. The crows gathered on electric wires, watching silently. The air was thick with the smell of burning ghee and incense. Distant temple bells clanged as Amma broke her bangles at the roadside grave.

Mother came to cry at my grave again and again. She brought marigolds and incense sticks, pressing her forehead to the cold mound, uncaring about the dust on her saree or the curious stares of rickshaw-walas passing by.

She wept so hard her body shook. Each sob seemed to come from her very soul, carving new lines into her face. She pressed her palms together, begging forgiveness from the sky.

She kept apologising, sometimes slapping her own face, wailing, “Why wasn’t it me who died?” Her voice rose and fell, desperate, as if the heavens might answer. She would pull at her hair, scratch at her arms, unable to bear the guilt.

Every time, I would try to comfort her: "Mummy, I don’t blame you. Please don’t cry anymore." My small, cold fingers tried to brush away her tears, wishing she could feel the touch of her daughter. I touched Amma’s feet, head bowed, seeking forgiveness, but she couldn’t feel me.

Her grief was a wall I could not cross. My words fell into the earth, unheard. I watched her leave, her saree pallu trailing in the dirt, head bowed low.

Father came a few times too. Always at dusk, alone, carrying a plastic bag of cheap toys and sweets. He never stayed long.

He brought dolls and small boxes of kaju katli, sitting before my small mound, stroking it as if patting my head. "Meera, I’m sorry… it’s Daddy’s fault." His hands trembled as he placed the toys on the earth, brushing away imaginary dust from the mound, as if tidying my hair. "These are the birthday presents I owe you for your ninth year. Daddy… still hasn’t taken you to the mela…"

The word ‘mela’ hung between us, heavy with memories—giant wheels, balloon sellers, sugarcane juice. I remembered tugging at his shirt, begging to go.

As he spoke, Father started to cry. His voice broke, his shoulders shook. Sometimes he buried his face in his palms, letting the tears soak his fingers, not caring if anyone saw. But when the aunty next door approached, he quickly cleared his throat, pretending to check his phone, hiding his grief.

The aunty next door stood behind him, patting his shoulder, saying, "Arre, what was her maa thinking? Who does that to their own child, haan?" Her bangles jingled as she reached for him, her voice sharp, glancing at Amma’s house with open disdain.

I lowered my head, feeling a little sad. I whispered, "But Aunty, you were the one who broke up our family first." My words floated, unheard, bitter with the memory of her forced sweetness—the kheer she brought during festivals now tasted like poison.

Father choked up and asked, "Meera, in the next life, will you be Daddy’s daughter again?" His voice trembled, hope flickering in his eyes as if my answer could save him. The silence between us was thick; I wanted to say yes, but the pain was too much.

Many people came to my grave: classmates, teachers, my best friends. Some wore their best frocks and uniforms, faces wet with tears. My best friend Anjali brought my favourite pencil box; even Mrs. Thomas, my class teacher, came, eyes swollen from crying.

They brought food I loved—packets of orange Parle-G, Kurkure, guavas sprinkled with chaat masala, and homemade besan laddoos crowded the little mound. My tiffin had never been so full in life.

They all cried. The air was thick with incense and tears. Some sobbed quietly, others howled, hugging each other for comfort.

I wanted to comfort them, to tell them not to be sad. I sat beside them, mimicking Amma’s gentle pats and strokes, wishing my touch could ease their pain.

But no one could see me, and no one could feel me. I was just a memory, a shadow on the edge of their world. Their love couldn’t reach me, and my love couldn’t reach them.

But deep inside, a new ache began—the ache of being truly forgotten.