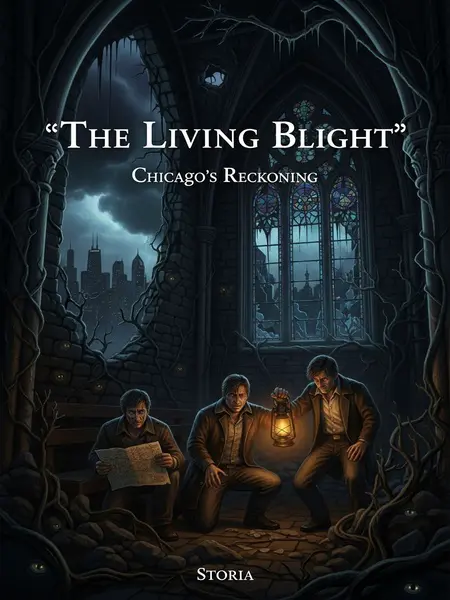

Chapter 5: Sins Unearthed

Marcus quickly asked, "What do you mean?"

He leaned in, voice urgent. The fire snapped, sparks flying up the chimney.

David said, "You both know, last year when the outbreak hit Chicago, I secretly fled the city. But you don’t know what I ran into outside. Even you, Eli, would’ve lost your mind!"

He paused, letting the words hang. The others waited, barely breathing, as David began his story.

Yeah, last year, when the dead piled up, I was scared out of my mind. On November 9th, right after Halloween, I used my connections to get out of Chicago, planning to hole up in Ohio.

I packed a duffel with cash, a couple changes of clothes, and an old family Bible. The city was a ghost town—sirens in the distance, the L trains running empty, every checkpoint a last warning. I never looked back.

But as soon as I hit Maple Heights, the countryside scared me worse than the city.

The silence was thicker—like the whole world had stopped breathing. No cars, no porch lights, just endless fields, grain silos looming in the dusk, and the smell of harvested corn hanging in the air.

That day, a heavy fog rolled in. I trudged the back roads, cold and hungry. Every town was dead silent—no one, not even a stray dog. It felt like the plague had wiped them all out. Even with a wallet full of cash, there was nowhere to spend it.

My stomach rumbled, hands numb from the cold. I knocked on doors, but got nothing. The only sound was the crunch of gravel and the far-off bark of a dog.

At dusk, I finally ran into a skinny old man at the entrance to a trailer park. He sat on a busted lawn chair, smoking a corncob pipe, looking like he’d been waiting for the end of the world.

He looked like he’d been there forever, pipe smoke curling around his head. His clothes hung loose, eyes sunken but stubborn. He looked like a piece of the prairie that refused to blow away.

I hurried over and asked where everyone had gone.

My voice sounded too loud in all that quiet. He didn’t look up, just kept puffing his pipe.

The old man didn’t look at me, just puffed and said, "Dead, all dead. Ain’t nobody left but me."

His words gave me chills. I glanced over my shoulder, half-expecting to see something moving in the fog.

I asked if he had any food.

My stomach twisted, the thought of another night without dinner made me desperate. I tried to sound casual, but my voice shook.

He took a drag, smacked his lips, and said, "Yeah, I got food."

He sounded almost amused, like sharing was a private joke. I tried not to take it the wrong way.

I quickly pulled out some cash. "Sir, I came from Chicago, haven’t eaten for days. If you got food, please, I’ll pay whatever you want."

I waved the bills, hoping money still meant something out here. But he just snorted.

He waved me off, still not looking up. "Don’t need it. I got food, but with nobody left, can’t finish it all myself."

He finally looked at me, eyes glassy but sharp. His voice was tired, like he’d given up on everything.

With that, he stood and shuffled down the road out of the trailer park.

His steps were slow but steady. I grabbed my bag and followed, hoping I wasn’t making a mistake.

I hurried after him.

My shoes slipped in the mud, but I kept up, heart pounding. The fog swallowed us, turning the world gray and strange.

He muttered as he walked, "Bad luck, real bad. Locusts came early, then the plague."

His words drifted back, each one heavier than the last. It sounded biblical, like the world was ending one disaster at a time.

I nodded along.

I didn’t know what else to do. The only thing scarier than his story was the thought of being alone again.

He kept talking: "When the locusts came, whole town starved. Lucky for me, my son’s in the city, so we sent word. He wrote back, said help was coming. We waited, but nothing came. My wife wanted to go find him, but I told her to wait. She agreed, but hunger’s a beast."

"I shouldn’t have, but I went out to the old plague chapel and dug up that evil thing in the basement. Been growing there God knows how long, like a ball of flesh. Old folks said just seeing it’d shorten your life, let alone eating it. But my wife was starving. Folks were eating anything—possums, raccoons. When you’re that hungry, nothing matters. I just wanted her to last until our son came."

"So one night, I snuck into the chapel and dug it up."

"But after my wife ate it, she changed. Her eyes went bird-like, her hands too. She started acting crazy. Worse, everyone who came near her got sick, puking up bloody lumps just like the thing I dug up."

"I locked her in, but she kept yelling to go find our son. Then I got sick, couldn’t watch her. One night, she ran off. Never came back, neither did our boy."

"Neighbors blamed my wife for the sickness. They wouldn’t let me leave. So I stayed, waiting for the city’s help. But one by one, everyone died—except me. It’s a curse—I’m the only one left. Plague everywhere, so I wait here for my wife."

His voice shook, words tumbling out. I saw the pain in his face, the guilt that clung to him like a shadow.

A chill ran down my spine.