Chapter 3: Whispers and Warnings

Figuring out why the Lal couple were killed was very important.

Inspector Prakash called us all for an emergency meeting at the chowki, his eyes bloodshot. "Yeh toh samajhna hoga, warna agla number kisi ka bhi ho sakta hai."

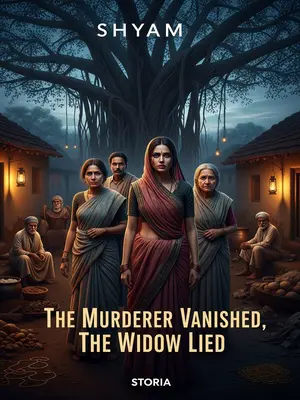

Whether or not Ananya did it, it revealed a major hidden danger—

No one was safe. The village, already shaken, now lived in terror. The sense of community that once held them together was crumbling by the hour.

If the Lal couple could be killed, could there be more victims?

People began whispering that the village was cursed. Mothers would not let their children out after sundown. The local temple saw more offerings in two days than in the past two months.

This was our greatest concern.

We doubled patrols, set up night watches, and asked the village elders to keep an eye out. But fear has a way of slipping past every lock and door.

After sending the bodies for post-mortem, Inspector Prakash led us to station ourselves in the village, staying at the local police chowki.

Our sleeping mats were spread on the cold cement floor, the constant buzz of mosquitoes our only lullaby. The chowki was a cramped, crumbling affair, but it was safer than anywhere else.

This hillside village was far from the district headquarters; the mountain road alone took nearly an hour by jeep.

On rainy days, the mud would swallow the tyres, and at every hairpin bend, the jeep threatened to tip. We grew used to the sound of monkeys on the roof and the distant howl of jackals.

Only our department’s jeep could make it—small cars might stall on some sections.

We’d joke about it, but inside, everyone knew that if trouble struck, help would be hours away. The village was on its own.

That’s also why, after the first family’s murder, we spent an entire day with little progress—most of our time was spent on the road.

The villagers grumbled, "Sarkari log hamesha late hi aate hain," but no one understood how much we depended on that battered jeep.

So moving into the village was the best option.

At least now we could act quickly, and the sight of uniformed men brought a measure of comfort to the terrified villagers.

First, it made it easier to continue searching for Ananya. Second, it might deter the killer and prevent further murders.

Inspector Prakash ordered a night patrol, torch beams slicing through the darkness as we moved from one house to another, sometimes stepping over sleeping cattle in narrow lanes.

Inspector Prakash also warned us that this village was very peculiar.

He lowered his voice, “Yahan ke log kuchh chhupa rahe hain, mujhe yakeen hai.” He’d seen enough to know when a village was hiding something.

Because the road was so rough, the village was isolated; we shouldn’t trust anyone there.

Even the postman came only once a week, and news from the outside world took days to arrive. In such a place, secrets were buried deep.

At the time, I didn’t understand why he said this.

Looking back now, I realize he was right. The village was not just isolated by geography, but by something darker—an unspoken pact of silence.

Next, we were extremely busy, as we had to start visiting every household in the village.

The monsoon clouds gathered above as we trudged from one home to the next, our boots caked in mud. At every doorstep, anxious eyes peered from behind curtains, unwilling to let us in, yet too afraid to refuse.

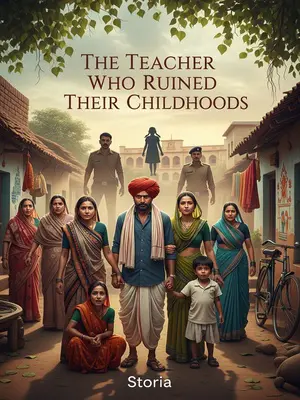

You have to understand, this was a hillside village—houses could be close together or scattered far apart, and there were even dwellings in unexpected places.

Some homes were built into the very hillside, barely visible from the main path. Others sat alone at the edge of the jungle, smoke curling up from their thatched roofs. The distant call of a koel mingled with the clatter of a pressure cooker somewhere uphill.

Inspector Prakash asked the village sarpanch to help, and he found someone to guide us so our visits could proceed smoothly.

The sarpanch, a burly man with a thick moustache and a voice that carried across the fields, seemed eager to cooperate. But there was a nervousness in his eyes that didn’t escape us.

By coincidence, I was following Inspector Prakash, with the sarpanch leading us on the rounds.

My notepad felt heavy in my pocket as we made our way through narrow lanes, the sarpanch pausing every so often to greet villagers, his tone too cheerful for the situation.

At one home, we encountered something strange.

The moment we stepped inside, the air felt different—stale and heavy, as if secrets lived in the very walls.

In this family, there was a madwoman.

She sat by the kitchen hearth, muttering to herself, fingers worrying the end of her faded sari. Her hair was wild, her feet bare and dirty. She stared at the smoke curling from the chulha, eyes following the gray wisps as if searching for answers.

She said some odd things, but they made us think of Ananya.

Her words came out in gasps, barely audible, but the few we caught made our hearts race. The children in the house stared at us, wide-eyed and silent.

This family’s situation was unusual. The man, Hariram, was a farmer in his fifties.

Hariram greeted us with a nervous smile, wiping his hands on his dhoti. His skin was tanned from years in the sun, and his eyes shifted constantly, never quite meeting ours.

But his wife, Lakshmi, was nearly twenty years younger.

Lakshmi looked much older than her age, her face lined by hardship and something deeper—perhaps fear, perhaps sorrow.

She had dishevelled hair, was dirty, and her expression was unnaturally vacant.

Some said she’d been that way since a fever in childhood, others blamed black magic or a family curse. Either way, she was the house’s ghost, moving in slow, silent circles.

The sarpanch told us she was mentally disabled since childhood and warned us not to pay attention to her nonsense.

He waved a dismissive hand, “Yeh toh pagal hai. Kuch bhi bolti hai, aap log mat suno.” But I noticed the nervous glance he shot Hariram, as if warning him not to let anything slip.

But the strangeness didn’t end there—they also had three children, aged ten, eight, and five.

The little ones clung to their mother’s sari, peeking out at us like frightened squirrels. The oldest boy’s eyes were far too old for his face.

The children were all timid, but didn’t seem to have inherited their mother’s disability.

They answered our questions in soft, polite voices, always looking to their father for approval before speaking.

It was the mentally disabled Lakshmi who, when no one else was paying attention, quietly whispered a few words to me:

She reached out suddenly, clutching my sleeve, her voice a mere breath. I bent closer, her words chilling me to the bone.

“Escape… she wants to escape… she escaped…”

Her eyes darted around, terrified, as if the very walls might be listening. My pen slipped from my hand. A silence fell, broken only by the distant clatter of a bucket at the handpump.

“Caught… caught…”

The word hung in the air. She clamped her hand over her mouth, shaking. A katori slipped from the shelf behind her and landed with a clang, making everyone jump.

I understood immediately, and a suspicion formed in my mind.

I glanced at Hariram. For a moment, I saw something flash in his eyes—a flicker of fear, maybe guilt.

Just as Lakshmi was mumbling “caught,” her husband Hariram noticed.

He crossed the room in two quick strides, voice low but hard as stone. His hand tightened around her arm.

In that moment, I could clearly see the honest look on Hariram’s face vanish.

The mask slipped. His jaw clenched, and for a heartbeat, he looked ready to do anything to keep her quiet.

But with us present, he didn’t act immediately; instead, he pulled Lakshmi away with a dark expression, muttering under his breath:

“Pagal aurat… chup ho ja… hamesha bakwaas karti hai…”

His voice was menacing, the words rolling off his tongue like a curse. The children shrank further into the shadows.

I was stunned.

I felt a chill creep up my spine. The house was no longer just strange—it was dangerous.

The sarpanch quickly tried to smooth things over:

“She’s not right in the head. If you don’t scold her hard, she won’t learn—always creating a scene. Don’t mind her…”

He forced a laugh, but his eyes were wary, watching us closely for any sign of doubt.

But I could clearly see Lakshmi’s pupils suddenly contract, her eyelids trembling.

She stared at me, pleading silently, as if begging me to listen, to believe her.

Her chapped lips opened and closed, but not a sound came out.

It was as if the words were stuck in her throat, held back by years of fear. Her whole body shook with the effort of staying silent.

Obviously, this was a pitiful reflex, as if she were a frightened bird—helpless and terrified.

She was the embodiment of all the secrets this village had buried. I wanted to reach out, but Hariram’s glare kept me rooted to the spot.

At that moment, I began to suspect that in this village…

I felt a weight settle on my chest. Something was very wrong here—something that went beyond a simple murder case. The village itself seemed to be hiding its own guilt.

The murders might not be accidental.

For the first time, I wondered if Ananya had really acted alone. Or if she, too, had been caught in a web spun by the very people who now trembled at the sound of our boots.

When I returned to the police chowki in the village, I reported to Inspector Prakash what I had found.

The old ceiling fan whirred overhead as I laid out every detail—Lakshmi’s whispered warnings, Hariram’s sudden anger, the sarpanch’s nervous laughter. Inspector Prakash listened without interruption, fingers drumming on the table. When I finished, he leaned back, his eyes dark with thought. “Yahan kuch aur chal raha hai, beta. Yeh sirf khoon ka mamla nahi hai… yeh gaon apna sach chhupa raha hai.”

Outside, the monsoon wind rustled the neem leaves, carrying with it secrets, and perhaps, the scent of justice yet to come.