Chapter 2: Bitter Kiln Shadows

After the war, as e dey be, dem suppose send all camp women into the bitter kilns.

The words alone fit make your skin crawl. Everybody for the camp sabi wetin e mean: a place so wicked, the air dey burn skin. Some women dey whisper stories of those wey enter and no come out. Even soldiers dey fear look us for eye.

That place na hell—smoke dey rise day and night, the air dey hot like pepper soup fire. Old, young, mad people—everybody dey suffer. Na no be place for human being at all.

People talk say the kilns dey behind the big city wall, where smoke no dey stop and cry dey vanish into ash. Dem say ground for there no dey drink water—everywhere just dry, like heart of wicked men.

So, three days ago, all the younger girls begin try their luck to follow soldiers.

From morning till dusk, camp turn to one silent market. Girls dey comb hair, rub palm oil to shine skin, borrow wrapper—even old ones—to look fine. Laughter mix with tears. Some dey pray to ancestors, others just dey hope.

These men wey survive war, after victory, dem dey return house go chop reward. Even if dem get wife, to carry second wife or keep woman no bad for us.

Nobody dey judge—survival na the only law wey matter. Wife for house, woman for road—no big deal. Some women just wan avoid bitter kiln. Others dey pray for small kindness.

When Musa Garba show, na because one useless man wan carry me go as wife. After I refuse, the man vex, throw me for bed inside tent.

The struggle dirty. Him breath smell like burukutu, hands rough and heavy. My voice die for throat as I try fight back.

"Nonsense. Daughter of criminal, camp woman, you still dey do like say you be correct young lady? When young captain dey, I no fit touch you. Now, na my turn..."

Him words slap me harder than hand, spit out all the hatred world keep for me. Shame and anger dey swell for chest.

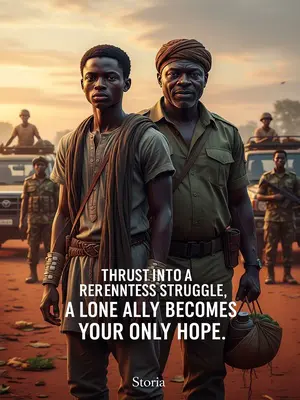

Before he fit finish, person just grab am for collar, throw am for ground.

Like thunder strike from nowhere. I hear grunt as he land, pride shatter with him yelp.

I jump up, fear catch me, na Musa Garba I see.

Him presence fill tent like Ogun himself enter. Eyes sharp, voice silent, but muscles dey flex warning. He look me, and for once, I feel shielded.

He drag the man outside like say na chicken.

I watch the ease wey he fling the man—no be small thing. Strength for him arm different from ordinary soldier. I start to believe some people really get power for this world.

At first, I hear the man dey shout outside, but e quiet quick.

One quick slap, struggle stop. Camp women, old and young, listen for that silence—the kind wey follow real danger. I know Musa Garba don settle am.

After he deal with the man, Musa Garba come back, stand for entrance like mountain, block all the light.

Him skin dark like roasted yam, strong everywhere. Sweat dey run from neck go down chest. He dey breathe heavy, just dey look me, but e no talk.

He carry whole heat of the day for him body, and silence deep like bottom of River Niger. I feel safe and exposed.

I no even know how long pass.

Time slow, air between us thick with words unsaid. I wait, heart dey beat fast.

He finally talk.

"I fit carry you."

E sound somehow, but I sabi wetin he mean.

Voice deep, steady, but no wickedness. Something for tone make my body relax small.

These days, no be only that idiot, like five or six men don come, say dem fit carry me go, some even promise say dem go make me main wife.

Each offer sound the same—desperation and hope. Some show trinkets, others brag of farm. All I see na way out of pain, not love.

After all, I be former pikin of Commissioner of Finance, sabi talking drum, ayo, writing, drawing. My beauty that year sweet for Aba, but now, even my shadow dey hide.

I reject all of them before.

Hope and pride warred inside me. My chest tight like wrapper tied too hard. I still dey wait, foolishly.

But this time, I look Musa Garba for face, he sharply shift eye.

Him face strong like person wey dem owe money, but I see say him ear don red.

Him shyness surprise me. For all the strength, he no fit look my eye. That small embarrassment make am human.

"I go think am."

Na so I talk.

Voice low, but my mind dey turn like okada wey lose control for muddy road. For the first time, I see door open, even if room behind am strange.

After Musa Garba commot, weak voice come from one corner.

Air heavy, but old woman voice cut through like knife for okra.

"He fit be the last one."

Na the only other person wey remain, old woman, wey sickness don nearly finish.

Her breath rattled, eyes watery but sharp. She watch me like mother goat dey eye stubborn pikin.

She laugh at me.

Her laughter no wicked, just tired, as if she don see this story play out many times.

"Ngozi, since person wan carry you go, abeg go. Who you dey wait for? That young Captain Folarin, wey wan marry governor pikin so?"

Pity dey for her eye, mix with resignation. She wan make I wise, no proud.

She sabi say me and Folarin get something.

If not, as camp woman, I no for escape from serving all those men.

She see the way I carry myself, the way even guards treat me. She never ask details, but her old eye miss nothing.

Every two days, I dey go out for night with my talking drum.

Some nights, guards let me pass, face soft with respect. Others dey look with envy, wish say dem fit get my kind privilege.

Only person like Folarin fit give that kind privilege.

She believe say Folarin just dey use me play, say make I no dey dream for person wey dey higher than me.

She sigh, as if wishing she fit shield me from my own foolishness.

But she no know say, na him no wan let go, no be me.

I don try leave before, but Folarin always find way draw me back. Na him hold, not my stubbornness, chain me for here.

As I close my eyes, I hear the drums—no be festival, but the sound of new beginning.