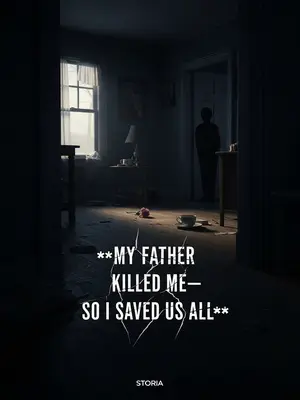

Chapter 1: Dead Is Dead—And So Was I

My mom has two sons. She says her younger son is hopeless, a real disappointment. Only the older son makes her happy. And yeah, I’m that hopeless younger son she’s always talking about.

Sometimes, when I hear her say it, her words cut sharper than a winter wind. It’s like she doesn’t even care that I’m standing right there, like I’m just some shadow in the corner. The words hang in the air, heavy and cold, and I wonder how many times I have to hear them before they stop hurting.

To prove myself, I always rushed to do the chores around the house and the work out in the fields, and whenever there was something good—like a fresh pie or a new shirt—I thought of my older brother first. That’s how it worked in our house: the younger one gave things up for the older. Later, after we divided up the family property, my mom showed up at my door with her bedding and moved in—she stayed for twelve years.

I remember those days like they happened yesterday. My hands cracked and raw from hauling firewood, the sunburn on my neck from working the rows of corn. Sometimes I’d think, What am I even doing this for? I’d come home aching, but if there was a treat or something new, I’d hand it over to my brother without thinking twice. Even after the family divided up—when she brought her old patchwork quilt and that battered suitcase—I just opened the door and tried to be the good son she never thought I was.

She criticized me every day. Made things hard for my wife. Treated my daughter harshly. I swallowed it all without a word. Even when I turned forty and my mom was paralyzed, my wife and I took turns carrying her piggyback out to the cornfields.

It got so routine it felt like breathing. Her sharp voice echoing down the hall, the way my wife would flinch when she heard footsteps, my daughter shrinking away from her glare. Even when my back ached and my lungs burned, I’d hoist her up and carry her out to the fields, pretending it was just what a son ought to do. We never complained. We just endured.

Later, when my black lung disease flared up—coal country problems, you know—my mom clung to her checkbook. Wouldn’t let go. Insisted the old town doctor make me drink some weird herbal remedy. As I lay dying, my mom drove my wife and sixteen-year-old daughter out of the house, then signed over the family’s apple orchard lease and our home to my sister-in-law’s family.

I remember lying there, every breath a struggle, and watching her count out her money like it was the only thing that mattered. She wouldn’t pay for my medicine. Not a dime. I couldn’t believe it. She’d rather trust some backwoods remedy than help me see a real doctor. And when I was too weak to fight back, she pushed my family out and handed over everything we’d built to my brother’s wife. It was like I never existed.

“Useless waste of space. Dead is dead. Good thing I held onto his money—didn’t let him spend a cent.”

Her voice was cold as the grave, every word a slap. I could almost see her lips curl as she counted the bills, as if dying was just another inconvenience I’d brought her. I hated her for it, right then.

“The only reason I stayed with him was so I wouldn’t be a burden on you all.”

Always the victim. Did she even hear herself? She played the martyr while she ruined us. She told that story so often, I think she believed it.

“Well, now everything in the house is yours.”

The words stung, even though I was barely conscious. She said it like she was tossing out trash, not a life’s worth of memories. Unbelievable.