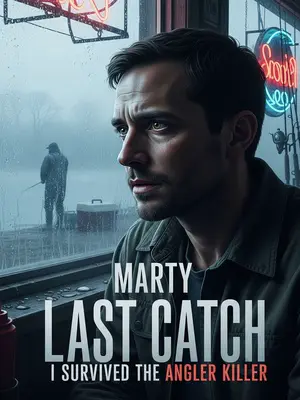

Chapter 1: The River’s Chosen

I was pretty much born a water baby—always felt drawn to creeks, lakes, and rivers. Somehow, that turned into making a living pulling bodies out of them. Not exactly what most folks dream about, but here I am.

It’s not exactly the sort of thing you brag about at your high school reunion, but hey, it pays the bills. I mean, hell, I’ve always felt more at home with my boots in the mud by a riverbank than walking a city sidewalk. Something about water just calls to me. Always has, since I can remember.

Grandpa always said this was my destiny. Go figure.

He’d tell anybody who’d listen—usually while whittling on the porch—that our family had river mud in our veins. He’d give me that sideways grin, the one that made you feel like you were in on a secret only the river knew. Like the river whispered to us, and us alone.

But after Grandpa left town for a job, he came back real sick and never really recovered.

He used to be strong as an ox, the kind of man who could haul a canoe through a swamp without breaking a sweat. After that job, though, he looked like he’d aged twenty years overnight. Even the way he sipped his morning coffee changed—slow, careful, like he was worried there might be something hiding in the bottom of the cup.

After that, he laid down a new family rule: from then on, nobody in the Morgan family was allowed to fish out corpses. Not anymore.

He gathered us all in the living room, his voice shaking just a little, and declared it a Morgan law. Said we’d had enough trouble from the river for one lifetime. My mom tried to argue, but Grandpa wouldn’t budge. He looked each of us dead in the eye, just to make sure we knew he wasn’t kidding around.

Still, to pay for his doctor’s bills, I started picking up jobs on the side, kept it quiet.

I figured if the river wanted me, it would’ve taken me a long time ago. Besides, hospitals don’t care about family rules when the bills come due. So I set up a burner email and started answering the kind of job postings most folks wouldn’t touch with a ten-foot pole.

When the Mississippi flooded, my mom was pregnant with me and couldn’t get out in time. My dad dove in to save her.

That was the summer of ‘99, when the levees broke and the whole county went underwater. Folks still talk about it at the diner—how the river swallowed the town and nearly took the Morgan family with it. Sometimes I can almost hear their voices, low and awed, like it happened yesterday.

By the time the neighbors pulled them out, they were both gone.

They say it happened quick. One minute, my dad was on the porch yelling for help; the next, the current had swept them both away. Neighbors waded out, but by then, it was too late.

But my uncle, sharp-eyed as ever, noticed my mom’s belly was still moving, even though she’d stopped breathing.

He always swore he saw a little ripple, like something was fighting to get out. He didn’t hesitate. Cut her open right there on the muddy bank. Hands shaking, praying to God he wasn’t too late.

That’s how I came into the world.

I was born blue and silent, or so they told me, but I started wailing before anyone could even wrap me in a towel. Folks called it a miracle. Grandpa just said it was the river giving back what it owed.

Grandpa always said I was born tough. Said my fate was tied to the water—meant for this trade, whether I liked it or not. Sometimes I wonder if he was right.

He’d tell me that story every birthday, his eyes shining, proud and maybe a little sad. “You’re river-born, kid. That means you’re stronger than most.”

Not just anyone can be a body fisher. There are all sorts of rules to follow.

You don’t just wade in and hope for the best. There’s tradition, superstition, and a whole lot of hard-earned wisdom that only comes from years spent knee-deep in the current. Grandpa kept a little notebook of rules—never go in alone. Never work on Sundays. Always leave a coin for the dead.

When I first started, Grandpa made me soak for seven days and nights in the 'body pool' behind the house, where dead deer and whatever chemicals he poured in floated together.

The pool was just an old livestock trough, stained with years of muck. He’d fill it with cold water, toss in a bottle of formaldehyde, and drop in whatever critter the river claimed that week. I remember the smell—sharp, chemical, and under it all, the sweet rot of death.

He said it was to get rid of any fear of death. As if that was even possible.

He’d sit by the pool at night, keeping watch with a lantern. Sometimes he’d tell stories about the ones who didn’t make it through the seven days. “You gotta look death in the eye, boy,” he’d say. “Or it’ll sneak up and take you when you’re not looking.”

Plenty of folks, even the tough ones, get scared off at this stage.

I heard about a cousin who lasted three days before bolting for the hills. Folks in town whispered about that pool—said it was haunted, cursed, or both. Grandpa just called it a test. Like if you made it, you were in the club for life.

Honestly, I was so young back then, I didn’t really get what death meant. So naturally, I wasn’t afraid. Not really.

At seven years old, death was just a word grown-ups used when they thought you weren’t listening. I spent most of my time splashing around, pretending to be a catfish. The only thing that scared me was the snapping turtles.

Plus, my nose barely worked. When the sun came up on the eighth day, I walked out and saw Grandpa grinning. I was officially his successor.

He wrapped me in an old army blanket and handed me a steaming mug of cocoa. “You did good, kid,” he said, clapping me on the back. I could see the relief in his eyes—like he’d been holding his breath all week, waiting to see if the river would take me too.

Being born for the water, I was a natural swimmer. I grew up fishing with Grandpa. We lived a quiet life in Maple Heights.

We spent long summers on the lake, lines cast, talking about everything and nothing. Grandpa let me steer the boat, teaching me to read the water the way other kids learned to read street signs. Maple Heights was the kind of place where everybody knew your name and your business—especially if your business involved the dead. Folks never forgot a thing.

But then, everything changed.

A storm rolled in that fall, and with it, a feeling like the whole world was shifting under my feet. Grandpa’s cough got worse, the jobs dried up, and the river seemed to be watching me with new eyes—like it was sizing me up.

My ancestors weren’t just fishermen—they were body fishers too.

It was a family secret, passed down like a recipe for cornbread or the right way to patch a leaky roof. We caught fish to feed the living, and pulled bodies to give peace to the dead. Grandpa always said you had to respect both sides of the river.

Grandpa had been in the business for decades and never screwed up. Not once.

He was a legend in three counties—people called him when the sheriff’s department gave up. He’d never lost a body, never left a family waiting longer than necessary. Folks brought him whiskey at Christmas and pie in the spring, just to say thanks.

But ever since he came back from that job out of state, it was like his very soul had been drained. His body wasted away. He lay in bed like a dried-up husk, barely more than a shadow.

He stopped talking, stopped eating, just stared at the ceiling like he could see something none of us could. The house felt colder with him like that, like winter had moved in early and refused to leave. I felt it too, deep in my bones.

He called me to his bedside and set down the family rule: no more body fishing for the Morgans.

He made me promise, his hand gripping mine so tight it hurt. “No more, you hear me? Let the river keep what it wants.”

But to pay for his doctor’s bills, I kept taking jobs online in secret.

I told myself it was just until the bills were paid, just until Grandpa was back on his feet. But the jobs kept coming, and I kept answering. The guilt sat heavy on my chest. Still, I couldn’t stop.

This latest job came from a client down South. Didn’t sit right with me, but I needed the cash.

His messages were always short, never used his real name. The way he wrote made me think he was used to getting his way—and used to hiding things, too.

He was secretive, wouldn’t say who he was or why he needed a body recovered.

No details, no photos, just a location and a promise of cash. I should’ve walked away, but there was something in the way he worded things—urgent, almost desperate.

Normally, jobs like this are a bad idea—they’re magnets for trouble.

Every old-timer in the business has a story about a job gone wrong—a body that wasn’t really dead, a client who vanished without paying, a river that refused to give up its secrets. I tried to tell myself I’d be careful. No mistakes this time.

But the price he offered was too good to refuse.

He wired half up front—enough to cover two months of Grandpa’s meds. I couldn’t say no. Not with that kind of money on the table. I’d never seen that many zeroes in my account before.