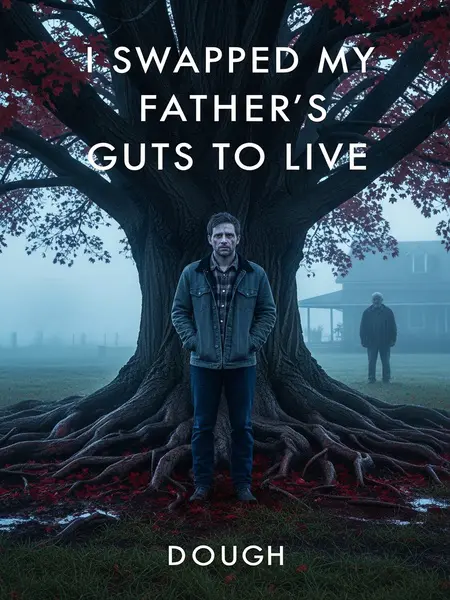

Chapter 2: The Maple Tree’s Secret

I celebrated my seventieth birthday back in my old hometown, Silver Hollow. Funny how things come full circle.

The party was held in the church basement, the kind with folding tables and those scratchy metal chairs. My wife, Martha, had spent all week fussing over casseroles and sheet cake. The place smelled like coffee and old wood. Smelled like every church basement I’d ever known. I hadn’t been back in decades, but folks still remembered me—the Douglas boy who left for the city and came back gray at the temples.

At the party, everyone toasted me, talking me up, joking, “You weren’t back long before a big old maple started growing in your yard, huh?”

They passed around red Solo cups, filling them with sweet tea and cheap whiskey. The old men winked and the women clucked their tongues. “That tree of yours, it’s a real monster,” someone said, raising a glass. “You must’ve brought some city magic back with you.” Big talk for a little town.

“That tree’s something else—huge and thick, and when the wind blows, it creaks and cracks. Scares folks half to death. And honestly? Sometimes it scares me, too.”

People laughed, but there was a nervous edge to it. In Silver Hollow, stories about trees that creak in the wind aren’t just stories—they’re warnings. Kids dare each other to touch its trunk after dark. Even the bravest dogs won’t pee on it.

I frowned, feeling something cold settle in my gut.

The laughter faded, just a little. My mind drifted back to the night I buried my dad. I sucked in a breath. The memory pressed against my chest like a stone.

Twenty years ago, I’d taken my dad’s intestines while he was still alive. For a second, I could taste the metallic tang of blood in the back of my throat.

Sometimes the memory comes at me out of nowhere, sharp and sudden. I see the blood, the way his chest rose and fell, the sound of his breath hitching. It’s like a stain that never washes out, no matter how many years go by. The smell, the heat, the guilt—always there.

After he died, I buried him in the yard. Just me and the shovel and the darkness.

It was a moonless night, the kind where the shadows swallow everything. I dug until my hands blistered, the shovel scraping against roots and rocks. The earth was cold and heavy, and every shovelful felt like it weighed a hundred pounds. I told myself I was doing right by him, but the guilt gnawed at me all the same. Still does.

But no one in Silver Hollow knew. Not yet, anyway.

I kept my head down, avoided questions. Folks in small towns talk, but they also know when to mind their own business—especially when it comes to the Douglas family. Sometimes secrets are the only things that survive.

I told everyone my dad had dementia, wandered off, and that I was heading to Chicago to look for him. Simple as that.

It was the perfect lie—plausible, tragic. People bought it. They brought casseroles, offered prayers, shook their heads in sympathy. No one ever looked too hard at the truth. Thank God.

And I was gone for twenty years. Just vanished.

Twenty years is a long time to stay away, but the city swallowed me up. Swallowed me whole, honestly. I worked odd jobs, kept my head down, sent the occasional postcard to Martha. Silver Hollow became a memory, distant and blurred, until I finally found the nerve to come back.

“Folks say maples are unlucky—ghost trees. Best not to mess with them.” That warning always comes up, sooner or later.

The conversation turned, as it always does in small towns, to superstition. “Maples are bad luck,” someone whispered. “They say if you plant one by your house, you’ll bring ghosts, you know?” I pretended to laugh, but my skin prickled.

Old Mr. Jenkins, my neighbor, stood up and toasted me with a wide, toothy grin. “But I’m not superstitious. Every now and then, I even trim the branches that hang over your fence.”

Jenkins wore his Sunday best—a plaid shirt tucked into faded jeans, suspenders straining over his belly. He winked at me, raising his glass. I could smell the bourbon on his breath from across the table. It hit me, strong and sour.

I shot Mr. Jenkins a look, my face tightening a little. I could feel the heat rise in my cheeks.

I knew exactly what he was after. Jenkins always had an angle. His grandson, Tyler, had just finished high school and was looking for a place to crash in the city. Jenkins figured a little flattery might grease the wheels. Classic.

I could practically see the wheels turning in his head. Small towns never change—everyone’s always working some angle, always looking for a leg up for their kin. Not that I blamed him, but still…

When I didn’t answer, Mr. Jenkins rubbed his nose awkwardly and added, “That maple tree in your yard, it’s really something. If I cut into the main trunk, it actually bleeds.”

Tried to play it casual, but his eyes kept darting to the window, like maybe the tree was listening in. “Swear to God, Doug. Took my hatchet to it last spring, and this red stuff came oozing out. Never seen anything like it.”

How could a tree bleed? I almost snorted. What a load. But the thought stuck, weird and sticky, right in the back of my mind.

The idea stuck in my mind, unsettling. Trees don’t bleed. Not like people do. I figured Jenkins was just spinning another yarn, the way he always did after a couple drinks. Ha. Same old Jenkins.

He’d always been a talker. The kind of guy who could turn a squirrel sighting into a ghost story by the time it made its way around the block. Still, the image of the bleeding tree wouldn’t leave me alone. Not for a second.

But my wife’s face went pale with fear. I saw her hands tremble, her lips pressed tight together.

Martha’s hands started to shake, her knuckles white around her napkin. She looked at me, eyes wide, lips pressed tight. I knew that look—it was the same one she’d worn the night my dad died. My stomach dropped.

On the table was a big platter—fried pork chitterlings. The steam rising, the smell hitting me in the face.

The smell was strong, greasy, the kind that clings to your clothes for days. The platter was heaped high, steam rising off the crispy bits. Folks around here loved them, but I couldn’t stomach the sight. God, just looking at it made me queasy.

Mr. Jenkins dug in, grease running down his chin, mumbling, “Why aren’t you eating?”

He licked his fingers, smacking his lips. “Best batch Martha’s ever made,” he said, shoveling another mouthful. “You’re missing out, Doug.” I felt my stomach twist.

My wife couldn’t hold it in anymore. Suddenly, she started gagging. Loud and sharp, like she was choking on her own breath.

The sound was sharp, cutting through the chatter. Martha doubled over, hand clapped to her mouth, eyes watering. The room went quiet, all eyes on her. My heart thudded in my chest.

The neighbors laughed. “Martha, you’re almost seventy—don’t tell us you’re pregnant?”

Someone snorted, and the tension broke. Laughter bubbled up, awkward and forced. But Martha wasn’t laughing—her face was ashen, her shoulders shaking. I felt a chill crawl down my spine.

She pressed her napkin to her lips, breathing hard. Sweat beaded on her forehead. She looked like she might faint right there at the table. I wanted to reach for her, but I just watched, frozen.

She kept retching, almost bringing up bile. It sounded awful—raw and desperate.

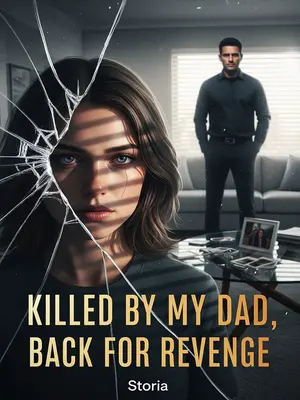

I reached for her, but she jerked away. Her whole body shook. I could see the memory flickering behind her eyes—she was thinking about what I’d done, the secret we’d buried together. Guilt, sharp and sudden.

I knew exactly what she was thinking—about what I’d done to my dad’s guts twenty years ago. It was like a silent accusation, hanging in the air.

It was written all over her face. Guilt, horror, disgust. I felt my own stomach turn. I wanted to tell her to pull herself together, to stop making a scene, but the words stuck in my throat. Damn.

I wasn’t happy. Not even close.

This was supposed to be my big day—a chance to show everyone I’d made it, that the Douglas name still meant something. But Martha was unraveling, and I could feel the eyes of Silver Hollow on me, judging, waiting for me to slip up. I wanted to disappear.

I’d planned this seventieth birthday in Silver Hollow just to show off a little. Looking back, maybe that was foolish.

I wanted folks to see I’d done alright, that I wasn’t the good-for-nothing kid they remembered. I wanted to stand tall, to bask in the glow of old friends and family. But instead, it was all falling apart. Figures.

But my wife wouldn’t play along. She just sat there, silent and shaking.

She sat there, face white as a sheet, mouth hanging open, the sour stench from deep in her gut filling the air. The shame burned through me.

She was making me look bad. I could feel my jaw clench, anger bubbling up.

I could feel the anger rising in my chest, hot and bitter. I clenched my fists under the table, willing her to snap out of it, to remember her place. But she just sat there, lost in her own terror. God, why now?

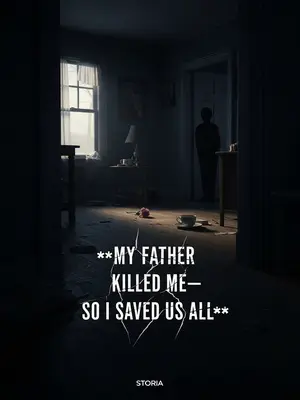

After the party, I shut the door and was about to smack her. My hand hovered, heart pounding.

The house was quiet, the only sound the hum of the old fridge. I turned to Martha, rage boiling over. My hand hovered in the air, trembling. For a split second, I wondered what I was doing.

Martha didn’t even notice my raised hand. Crying, she said, “After Dad died, his spirit was so angry. He turned into that tree, and the blood that seeps from it—that’s your dad’s blood!”

Her voice was thin, desperate. Tears streamed down her face. “I swear, Doug, I’ve seen things—shadows moving, whispers in the night. That tree’s not just a tree. It’s him, watching us.” The words echoed in the kitchen.

“Bull! Mr. Jenkins was just pulling your leg!” I snapped, voice sharp and raw.

I barked the words, trying to drown out her fear with anger. “You’re letting old wives’ tales get to you, Martha. There’s no such thing as haunted trees.” God, I was so tired of this.

Finally, my hand came down across her cheek. Shock hit me, but I couldn’t stop. “When people die, they just rot in the ground!”

The slap echoed in the kitchen. Martha staggered back, hand pressed to her cheek. My own hand stung, but I barely noticed. “That’s all there is to it. Dead is dead.”

Martha’s teeth weren’t great, and I hit her a little too hard. For a second, I just stared, horrified.

She gasped, a couple teeth clattering to the floor. Blood welled up, bright and shocking against the yellow linoleum. My stomach lurched, but I couldn’t show weakness now. Not now.

They rolled under the fridge, out of sight. Martha whimpered, tears streaming down her face. I felt a flicker of guilt, but I pushed it down. I couldn’t afford to lose control—not now. Not ever.

Blood dripped onto the old linoleum floor. The color was too bright, too real. I wanted to look away.

The drops spread into little red pools, seeping into the cracks. The kitchen smelled like iron and old soap. I stared at the mess, my mind spinning. Nausea crept up my throat.

She stared at the ground, terror in her eyes. “I saw it myself, back then—you cut your dad open right here and took out his guts.”

Her voice was barely a whisper, but it cut right through me. She was remembering everything—every sound, every smell, every terrible detail. I looked away, unable to meet her eyes. Her words echoed, hollow.

Yeah. That’s all I could manage. My throat was tight.

The memory pressed down on me like a weight. I nodded, once, not trusting myself to speak. The guilt, the shame, the regret—all of it choked me.

Back then, I’d sliced open my dad’s belly right on this floor. That image burned in my mind, refusing to fade.

The image wouldn’t leave me—the blood, the knife, the way my dad’s eyes opened at the last second. It played on a loop, haunting me every time I closed my eyes. Over and over.