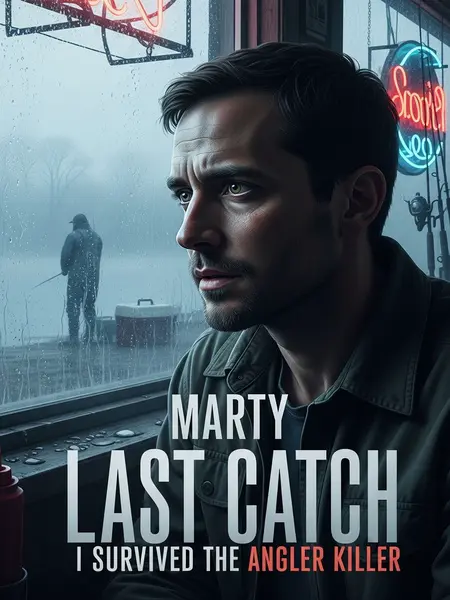

Chapter 2: When Fishermen Vanish

Anyway, the story started about two weeks ago.

It feels like a lifetime, looking back. Two weeks—just fourteen days—and everything changed. I guess that’s how it goes in a small town. Nothing happens for years, then everything hits at once.

Sheriff Donnelly and I were pretty close, mostly because we shared the same hobby—fishing.

We’d met at the county fair fishing contest a few years back. He’d ribbed me for using store-bought bait, and I’d given him hell for wearing his badge on his fishing vest. After that, we became fast friends.

Life in a small Midwestern town is slow; you don’t get many big cases all year.

Most days, the biggest excitement is a stray dog or a lost wallet. Folks know each other by name, and gossip travels faster than the wind. It’s the kind of place where you can leave your front door unlocked—well, used to, anyway.

Every few days, Donnelly and I would meet up by the river to fish.

Sometimes we’d just sit there for hours, barely talking, letting the water do the heavy lifting. Other times, we’d swap stories, complain about the weather, or argue about the best bait. It was our thing—a little escape from the grind.

But right before Labor Day, for ten days straight, every time I asked Donnelly to go fishing, he turned me down.

It was odd. Labor Day weekend is the Super Bowl for anglers around here. Donnelly never missed it. So when he started making excuses, I knew something was up.

Given his job, I figured something must’ve happened.

Cops don’t get to clock out, not in a town this size. If something big was brewing, he wouldn’t say, but you could see it in his eyes. He looked tired, distracted—like his mind was somewhere else.

Rumors started swirling. Folks said someone had died in the county, spinning all sorts of wild stories.

You know how it is—one person says “missing,” the next says “murder.” By the end of the week, people were whispering about serial killers and haunted woods. The grapevine was working overtime.

Donnelly told me they’d already gotten two reports—people had gone missing, no sign of them, dead or alive.

He kept it short, but the worry in his voice was clear. Missing people just don’t happen here—not like this. It spooked everyone, even the old-timers who claimed they’d seen it all.

He couldn’t share much more.

He just gave me that look—serious, heavy. I knew better than to push. He’d tell me what he could, when he could.

He just warned me to be extra careful if I went fishing.

His words stuck with me. “Don’t go alone, Marty. And if you see anything weird, you call me. Promise.” I promised, but I could tell he wasn’t convinced.

We only chatted for a few minutes before Donnelly hung up, sounding stressed.

He apologized, said he had paperwork to do, then hung up before I could ask anything else. I stared at my phone, feeling unsettled.

I may not know much about criminal investigations, but I understood how tough it’d be to crack a case like this.

Missing people, no leads, no evidence—it’s a nightmare for any cop. I tried to imagine what Donnelly was dealing with, but it was impossible.

The crucial seventy-two hours had already passed; with every hour that went by, it got harder to solve.

I remembered reading about that once—the first three days are critical. After that, odds get slim. It made the whole thing feel hopeless.

No one in the fishing crowd dared go out. I looked at my packed gear and sighed.

My tackle box sat by the door, rods leaning against the wall, collecting dust. The itch to get out on the water was strong, but fear kept me inside. I hated it.

But curiosity got the better of me.

I’ve never been great at leaving things alone. Even as a kid, I was the one poking the hornet’s nest just to see what would happen.

The town had been quiet for so long—how could people just start vanishing?

It didn’t add up. We’re not some big city with dark alleys and strangers on every corner. If someone was missing, someone else would notice. That’s how it’s always been.

I decided to try to 'accidentally' run into Donnelly, hoping to get more info.

I figured if I bumped into him somewhere public, maybe he’d let something slip. Or at least I could read his mood, see how bad things really were.

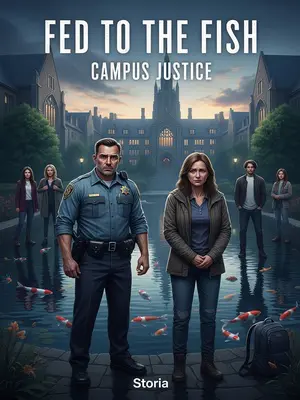

Around noon, I headed to a local sandwich shop.

It was the kind of place with faded linoleum floors and a bell that jingled when you walked in. The walls were covered in old photos—kids with fish, Ed with a trophy bass, the county softball team from ‘96.

It was about a quarter mile from the sheriff’s station, just across the main intersection.

You could see the courthouse from the parking lot. Sometimes, deputies would grab lunch there, still in uniform, trading jokes with the regulars.

It was our favorite spot. The owner, Big Ed, had a face weathered from years in the sun—one look, and you knew he’d spent half his life fishing.

His hands were big and calloused, with a handshake like a vise. He had this booming laugh that could fill the whole place.

It was lunchtime, and the place was packed, mostly with middle-aged guys, all with sunburned arms.

Some wore camo hats, others had sunglasses perched on their heads. You could spot the regulars by the way they teased Ed or claimed their usual seats.

The shop opened at 10 a.m. and stayed open until late at night.

Ed prided himself on being there for the early risers and the night owls. Sometimes, he’d swap out his apron for a fishing vest and disappear for hours, leaving his wife to run the show.

The portions were generous, the prices fair, and there were always folks waiting for a seat. A lot of fishing buddies loved to eat here—either before heading out or after packing up their rods.

The counter was lined with old coffee mugs, each one claimed by a regular. You could always find someone swapping stories about the one that got away.